BBC News NI

Omagh Bombing Inquiry

Omagh Bombing InquiryWarning: This story contains distressing details

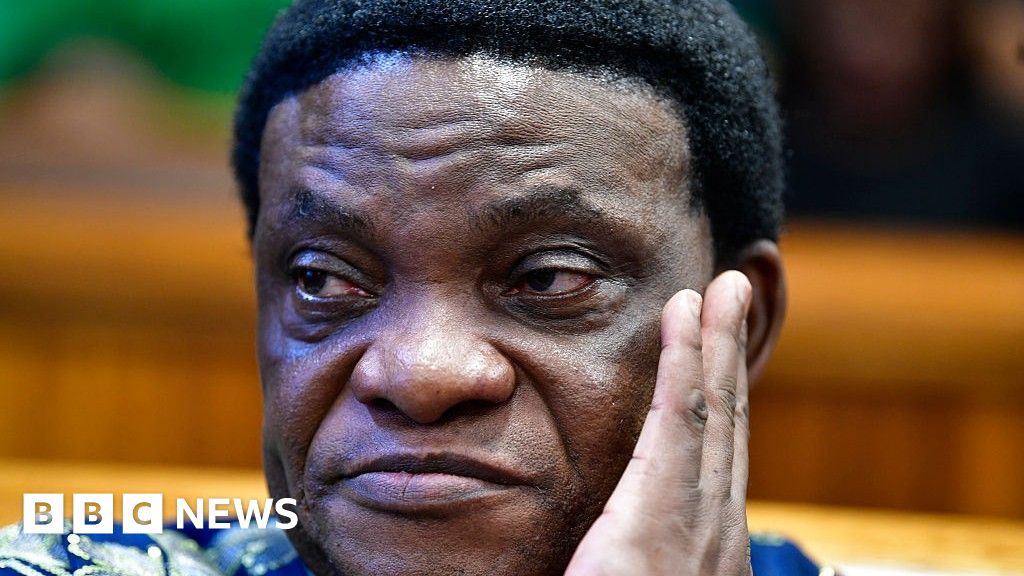

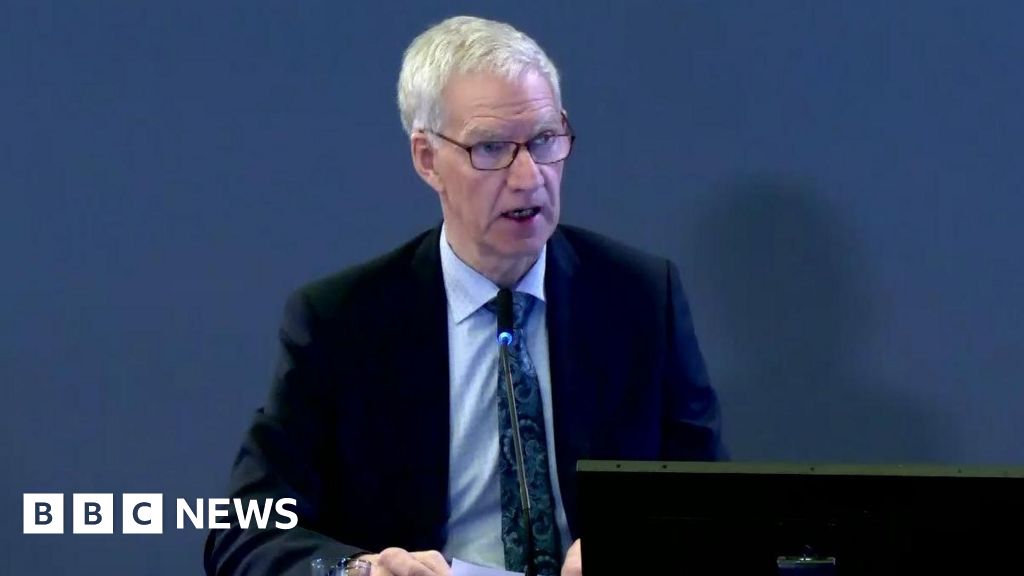

A senior RUC officer who led the police response to the 1998 Omagh bombing has described how he had to maintain a professional manner in response to the attack while also grieving a personal loss.

James Baxter, who was sub-divisional commander in Omagh at the time, told the public inquiry into the attack that his son’s girlfriend was killed that day.

“Whilst attempting to act in a professional manner I found too that I was grieving because of my son’s girlfriend’s death,” he said.

“My wife and I felt the loss very severely and as a family had to work through the many issues which emerged because of the bomb.”

The Real IRA bomb killed 29 people in the County Tyrone town in August 1998, including a woman who was pregnant with twins.

Mr Baxter said visiting the families of the bereaved in the aftermath of the attack had been “the most difficult and emotional duty” of his career.

He described how after visiting the family home of his son’s deceased girlfriend and sympathising with her mother, he left his son home and “immediately resumed duty”.

‘Very distressing’

Mr Baxter told the inquiry that he had been off-duty on the day of the attack and that when he was informed of the bomb threat to the Omagh Courthouse, he said he made his way back to Omagh “at speed” and implemented a major incident plan.

He said the sight of the bodies laid out in this temporary mortuary was “very distressing” and “brought home vividly the impact of the atrocity that had been inflicted on the people of Omagh”.

Mr Baxter also detailed the many hoax bomb threats that were made after the bomb, and how one individual was subsequently arrested in connection with more than 70 hoax bomb alerts.

He said the bomb and subsequent events had such an effect on his wellbeing that he cut his police career short and left the service in 2003.

What was the Omagh bomb?

PA Media

PA MediaThe bomb that devastated Omagh town centre in August 1998 was the biggest single atrocity in the history of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Twenty-nine people were killed, including nine children, a woman pregnant with twins, and three generations of one family.

It came less than three months after the people of Northern Ireland had voted yes to the Good Friday Agreement.

Who carried out the Omagh bombing?

Three days after the attack, the Real IRA released a statement claiming responsibility for the explosion.

It apologised to “civilian” victims and said its targets had been commercial.

Almost 27 years on, no-one has been convicted of carrying out the murders by a criminal court.

In 2009, a judge ruled that four men – Michael McKevitt, Liam Campbell, Colm Murphy and Seamus Daly – were all liable for the Omagh bomb.

The four men were ordered to pay a total of £1.6m in damages to the relatives, but appeals against the ruling delayed the compensation process.

A fifth man, Seamus McKenna, was acquitted in the civil action and died in a roofing accident in 2013.

The public inquiry

After years of campaigning by relatives, the public inquiry was set to up examine if the Real IRA attack could have been prevented by UK authorities.

This phase of the inquiry is continuing to hear powerful individual testimonies from relatives who lost loved ones in the explosion.

The bombers planned and launched the attack from the Republic of Ireland and the Irish government has promised to co-operate with the inquiry.

However, the victims’ relatives wanted the Irish government to order its own separate public inquiry.

Dublin previously indicated there was no new evidence to merit such a move.