BBC News, Marathi

BBC/Sharad Shankar Badhe

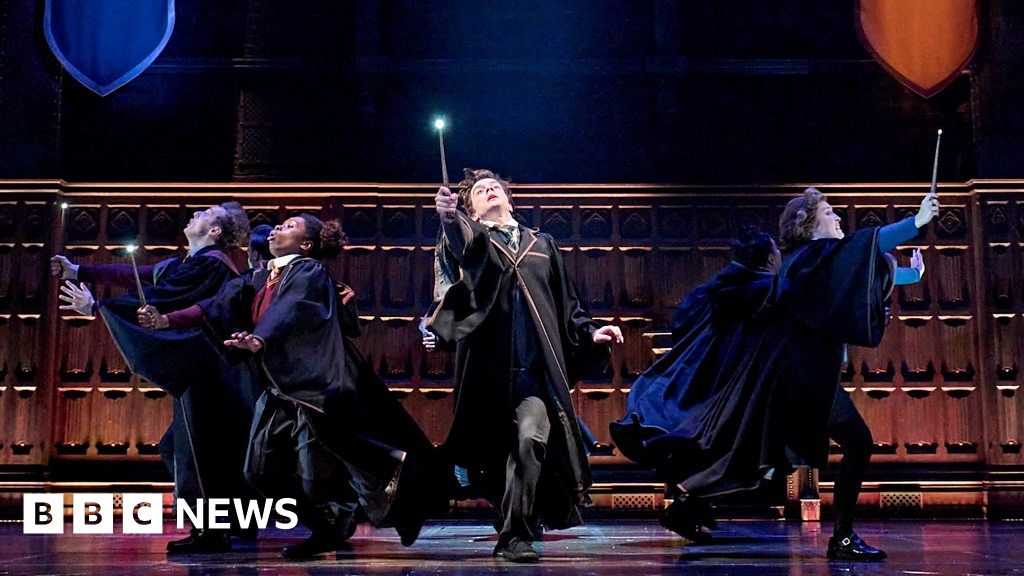

BBC/Sharad Shankar BadheIn his 1983 science fiction story, an Indian astrophysicist predicted what schools would look like in 2050.

Jayant Narlikar envisioned a scene where an alien, living among humans, would sit in front of a screen and attend online classes. The aliens are yet to manifest, but online classes became a reality for students far sooner, in 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic hit.

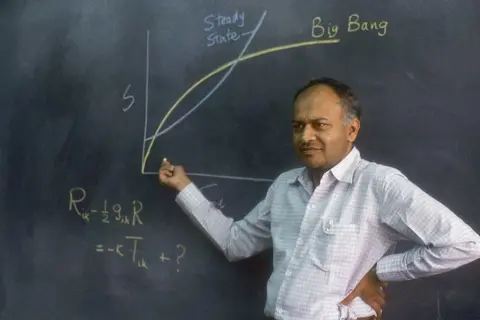

Narlikar also famously proposed an alternative to the Big Bang Theory – the popular idea that the universe was created in a single moment from a single point. He believed that the universe had always existed, expanding continuously into infinity.

With his passing on Tuesday, India lost one of its most celebrated astrophysicists. Narlikar was 86 – a man far ahead of his times and someone who shaped a generation of Indian researchers through his lifelong dedication to science education.

His funeral was attended by hundreds, from school children to renowned scientists and even his housekeeping staff, underscoring the profound impact he had on society.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBorn on 19 July, 1938, in the town of Kolhapur in the western state of Maharashtra, Narlikar was raised in a home steeped in academic tradition.

His father, Vishnu Narlikar, was a professor and mathematician, and mother Sumati was a scholar of the Sanskrit language.

Following in his parents footsteps, the studious Narlikar went to Cambridge University for higher studies where topped a highly prestigious mathematical course. He also took a deep interest in astrophysics and cosmology.

But his most significant episode at Cambridge was his association with his PhD guide, physicist Sir Fred Hoyle. Together, Narlikar and Hoyle laid the groundwork for a revolutionary alternative to the popular Big Bang theory.

The two physicists contested the Big Bang Theory, which posits that all matter and energy in the universe came into existence in one single instance about 13.8 billion years ago.

The Hoyle-Narlikar theory boldly proposed the continuous creation of new matter in an infinite universe. Their theory was based on what they called a quasi-steady state model.

In his autobiography, My Tale of Four Cities, Narlikar used a banking analogy to explain the theory.

“To understand this concept better, think of capital invested in a bank which offers a fixed rate of compound interest. That is, the interest accrued is constantly added to the capital which therefore grows too, along with the interest.”

He explained that the universe expanded like the capital with compound interest. However, as the name ‘steady state’ implies, the universe always looks the same to the observer.

Astronomer Somak Raychaudhury says that though Narlikar’s theory isn’t as popular as the Big Bang, it is still useful.

“He advanced mechanisms by which matter could be continually created and destroyed in an infinite universe,” Raychaudhary said.

“While the Big Bang model gained broader acceptance, many tools developed for the steady-state model remain useful today,” he added

Raychaudhary recollects that even after Hoyle began to entertain elements of the Big Bang theory, Narlikar remained committed to the steady-state theory.

A sign outside his office fittingly stated: “The Big Bang is an exploding myth.”

Arvind Paranjpye

Arvind ParanjpyeNarlikar stayed in the UK till 1971 as a Fellow at King’s College and a founding member of the Institute of Theoretical Astronomy.

As he shot to global fame in the astrophysics circles, the science community in India took note of his achievements.

In 1972, he returned to India and immediately took charge of the Theoretical Astrophysics Group at the coveted Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, which he led it till 1989.

But his biggest contribution to India was the creation of an institution dedicated to cutting-edge research and the democratisation of science.

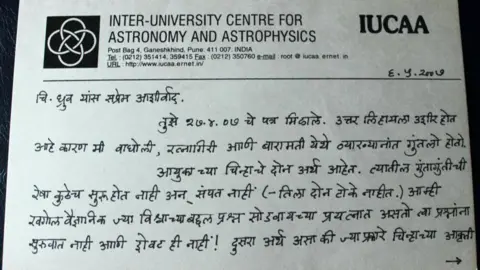

This dream materialised in 1988, when Narlikar, along with other distinguished scientists, founded the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA) in Pune city in western India.

From a modest 100sq ft room, IUCAA has gone on to become an internationally respected institution for astronomy and astrophysics.

Narlikar served as its founder-director till 2003, and continued to be an emeritus professor after that.

He insisted that IUCAA should include programs aimed at school children and the general public. Monthly lectures, science camps, and workshops became regular events.

Recalling Narlikar’s vision for the institution, science educator Arvind Gupta says, “He said PhD scholars don’t fall from the sky, you must catch them young. He offered me a place to stay, told me to try running the children’s science centre for six months, and I ended up staying 11 years. He gave me wings to fly.”

Despite being a prolific scholar who published over 300 research papers, Narlikar never confined himself to being just a scientist. He also authored many science fiction books that have been translated into multiple languages.

These stories were often grounded in scientific principles.

In a story called Virus, published in 2015, he envisioned a pandemic taking over the world; his 1986 book Waman Parat Na Ala (The Return of Vaman), tackled the ethical dilemmas of artificial intelligence.

Sanjeev Dhurandhar, who was part of the Indian team that contributed to the physical detection of gravitational waves in 2015, recalled how Narlikar inspired him to attempt the unthinkable.

“He gave me a complex problem early in my research. After I struggled for a week, he solved it on the board in 15 minutes – not to show superiority, but to guide and inspire. His openness to gravitational waves was what gave me the courage to pursue it.”

A well-known rationalist, Narlikar also took it upon himself to challenge pseudoscience. In 2008, he co-authored a paper that challenged astrology using a statistical method.

Raychaudhary said that his motivation to challenge pseudoscience came from the belief system of questioning everything that did not have a scientific basis.

But when it came to science, Narlikar believed in exploring the slimmest of possibilities.

In his last days, Narlikar continued doing what he loved most – replying to children’s letters and writing about science on his blog.