Nick Beake & Joshua Cheetham, BBC Verify in Washington

BBC

BBCThe US government and law enforcement agencies have hit out at developers and users of apps which track Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), arguing they threaten the lives of agents.

The FBI says the man who targeted an ICE facility in Dallas – killing two detainees – had used these types of apps to track the movements of agents and their vehicles.

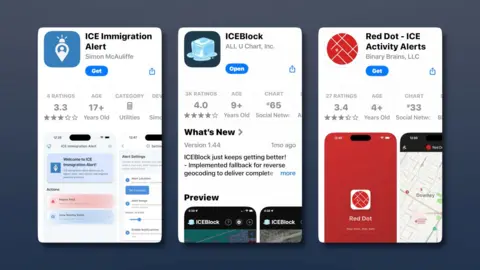

A tracking app downloaded more than a million times that shows the movements of immigration officers was removed from Apple’s App Store on Thursday.

ICE Block was released in April following the Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration. The creator of the app told the BBC that Apple was “capitulating to an authoritarian regime”.

The White House and the FBI had argued the app put the lives of law enforcement at risk.

Special Agent Joseph Rothrock said: “It’s no different than giving a hitman the location of their intended target” – a claim which has been disputed by the developer of one of the most popular apps.

BBC Verify has been looking at what the apps do and the potential impact they are having.

How do the ICE-tracking apps work?

A number of apps have been released this year in response to President Trump’s crackdown on illegal immigration and an upsurge in ICE raids.

The apps allow people to report the presence of ICE agents in their local areas which are then marked on a map to warn other users.

The most popular is ICEBlock, which was released in April and has been downloaded more than one million times.

It – and several other ICE-tracking apps – were abruptly removed from the Apple Store amid criticism from the Trump administration.

“We created the App Store to be a safe and trusted place to discover apps. Based on information we’ve received from law enforcement about the safety risks associated with ICEBlock, we have removed it and similar apps from the App Store,” Apple said in a statement.

Why were the apps set up?

Joshua Aaron – who has worked in the tech industry for years – told BBC Verify why he developed ICEBlock.

“I certainly watched pretty closely during Trump’s first administration and then I listened to the rhetoric during the campaign for the second. My brain started firing on what was going to happen and what I could do to keep people safe”, he said.

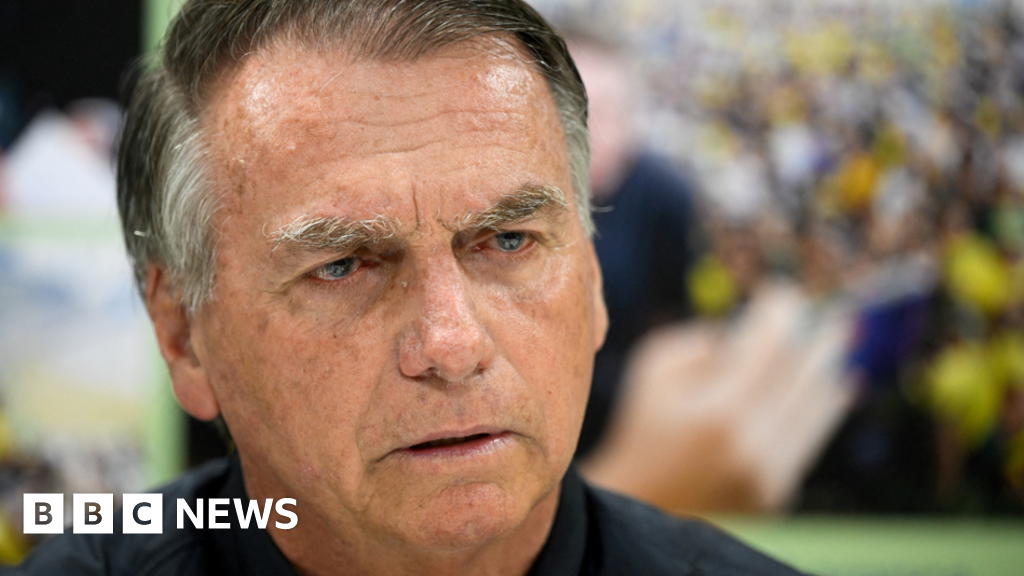

In July, US Attorney General Pam Bondi accused Mr Aaron of “threatening the lives of our law enforcement officers throughout this country.”

“We are looking at him, and he better watch out,” she added.

Mr Aaron said he was undeterred.

“Anything that challenges what they’re doing in this country and to this country, they’re going to push back on… but they’re not going to intimidate me. ICEBlock will be here for as long as it’s necessary.”

And he said specific criticism of him following the Dallas shooting was unjustified.

“You don’t need to use an app to tell you where an ICE agent is when you’re aiming at an ICE detention facility. Everybody knows that’s where ICE agents are.”

After the app was removed by Apple, Mr Aaron said he was “incredibly disappointed” and denied that the app could impact the security of law enforcement, which Apple had cited in its reasoning. He vowed to fight the move.

“ICEBlock is no different from crowd sourcing speed traps, which every notable mapping application, including Apple’s own Maps app,” he said. “This is protected speech under the first amendment of the United States Constitution.”

Who is using the apps?

The BBC spoke to several undocumented migrants in Washington DC who use the apps to avoid ICE officers.

“It’s scary. They could grab you anywhere,” one of them said.

“I don’t use it often but I think it can be useful. I’ve heard on the news that the government says it’s dangerous [to ICE agents] but I’ve never heard of something really ever happening, at least not around here,” he said.

Another said she found it hard to imagine a scenario in which an undocumented migrant would use the app to harm a law enforcement officer.

“We are here to work, and do not want problems. Nobody would want to make their situation here more difficult,” she added.

Another group appears to be using the apps for a different purpose.

On one popular Reddit thread, some users claim they deliberately feed fake information into the apps to try to thwart efforts to detect ICE operations.

One user said: “Sandbag it. Kick the anti-crowdsource into overdrive. Fun tip: it works better if you get a bunch of people to report the same wrong location.”

When we reached out to this user, they said “I think ICE is doing great work. I support everything ICE is doing. I think apps like that are interfering with constitutionally-authorised law enforcement activities. Deport, deport, deport.”

Reuters

ReutersWhy is the US government criticising these apps?

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) says there has been a 1,000% rise in attacks on ICE employees.

Fox News reported a near 700% rise in attacks from the first six months of 2024 to the same period in 2025. Assaults went up from 10 to 79.

We asked DHS for a breakdown of recorded attacks.

It did not provide these, but highlighted individual violent incidents against ICE agents including bomb threats, the use of cars “as a weapon” and a shooting.

ICE agents themselves have been accused of violence and misconduct.

On 26 September, DHS placed an officer on leave after he was filmed shoving a woman to the ground at a New York immigration court.

He has reportedly returned to duty.

Can the government ban the apps?

Marianna Poyares, from Georgetown Law’s Centre on Privacy and Technology, said they could be hard to ban.

“Laws that permit banning apps on national security grounds typically only apply to foreign-controlled technology, which doesn’t apply here as these apps are US-based.”

She argued that the apps are similar to police radio scanners, which allow the public to tune into police communications and are protected under the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

And she said that even if the government successfully banned the apps, the information would simply be shared on other platforms instead.

“The government does not have any power to crack down on the apps,” said Seth Stern, director of advocacy at Freedom of the Press Foundation.

“The fact that somebody might use the app to break the law doesn’t mean the app can be banned any more than a newspaper or radio station can be banned, because someone might use its reporting in a manner that the administration considers unlawful.”

“You punish the act,” he added. “You don’t ban the tools, especially when they’re constitutionally protected.”

Before his app was removed from Apple’s App Store, Joshua Aaron told us he was not aware of any pressure being put on Apple to remove it.

But he said he had faced death threats and harassment, including the sharing of his personal details online.

“I’m not going to live in fear, but I’m not going to be stupid. I mean, when I go outside my door, I look both ways.”

Additional reporting by Bernd Debusmann Jr, Aisha Sembhi & Lucy Gilder.