Alamy

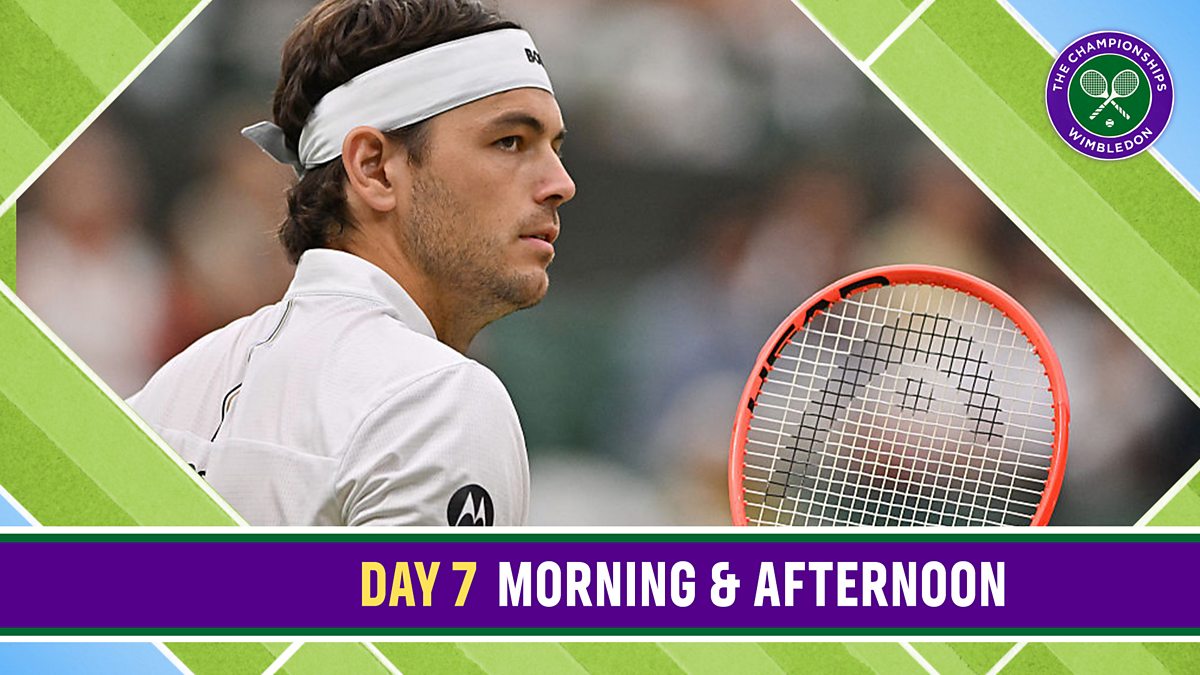

Alamy“I’m the messiah… I’m Marvel Jesus!” proclaims Ryan Reynolds’ Deadpool in his third lead outing as the acerbic, X-rated, genre-satirising anti-hero, who returns to cinemas on Thursday for the first time since 2018.

It’s a typically subversive line. But the sharpest jokes hold a grain of truth.

Disney’s Marvel franchise is not short of superheroes, but it is in need of saving right now.

Traditionally, heavyweights like Spider-Man, Thor, Hulk or the Avengers ensemble could be relied on to save the day. But these aren’t ordinary times for Marvel, following the studio’s much-discussed slump.

It’s a good thing, then, that Reynolds’ Deadpool has fully joined the fold, alongside Australian Hugh Jackman – who, thanks to the creative joys of the Marvel multiverse (parallel worlds of different realities), is able to reprise his iconic role as the late metal-clawed Wolverine.

A few years ago, even in the craziest timeline, a downturn in Marvel’s fortunes seemed unthinkable. In 2019, Avengers: Endgame alone took £2.1bn – a high point for the studio’s cinematic universe, which has earned Hollywood almost £23bn since 2008 in an eye-watering gold rush over 33 films.

But last year its iron grip loosened. The confusingly named The Marvels opened to a franchise record low of £38m.

Audience fatigue appeared heavy against an avalanche of interconnected multiverse content – from traditional blockbusters to TV series released on streaming over the pandemic.

This created “a muddled narrative that baffled viewers”, wrote Tatiana Siegel in a Variety feature headlined “Crisis at Marvel”. She described Marvel mastermind Kevin Feige as spread too thin across projects, struggling to maintain standards and ready to wield the axe.

Disney CEO Bob Iger publicly acknowledged quantity had “diluted” the brand, promising to rein in the sequel-heavy culture and put stories first.

Disney

DisneyEnter Reynolds, who, at a press conference earlier this month, emphasised the film’s unique identity – bringing edge and self-deprecation to an increasingly stale universe. As a co-writer and producer, he said he feels “immensely proud” to make “a different type of movie for the MCU”.

Speaking to the BBC, he says the messiah line reflected Deadpool’s enduring fortune to be “in the right place at the right time”.

“Those lines were written before any larger analysis of storytelling trends in the media,” he adds.

The film sees Deadpool trying to escape his superhero past. But his peaceful existence unravels when the MCU’s Time Variance Authority – the group entrusted to balance the dizzying multiverse timelines – finds itself out of control.

Its corporate stooge Mr Paradox, played by Succession’s Matthew Macfadyen, tries to covertly recruit Deadpool to help safeguard the central “sacred” timeline of reality by sacrificing his world. Refusing, he drags a begrudging, living, Wolverine into his timeline in a bid to save the day.

When asked about potential future spin-offs for the pair, Reynolds insists he wants to steer clear of Marvel’s recent pitfalls. “I love being able to do a movie that is in and of itself just a movie,” he tells the BBC. “Deadpool and Wolverine isn’t a commercial for another movie. It’s just not part of the DNA.”

‘Friends for decades’

Reynolds and Jackman have known each other for almost two decades, first working together in 2008 for X-Men Origins: Wolverine, which gave Reynolds his superhero start. Their friendship is clear.

“You’re so lucky because a lot of people don’t know how jealous Wolverine can be,” jokes Jackman. “If you mention anyone else, I will kill them. Particularly if it’s another Australian superhero.”

“You know, his claws come out…” jibes Reynolds.

“So Thor is out!” adds director Shawn Levy, in reference to Australian Chris Hemsworth.

Disney

DisneyThe exchange mirrors how Reynolds sees their real-world relationship reflected on screen. The Canadian star says it was “such a treat to write dialogue” for the film because it felt like “straddling this line – myself and Hugh speaking to each other as friends who’ve… been through a lot together.

“Hugh and I are very outwardly jokey, but in real life our conversations are intense and emotional and about life and all kinds of stuff.”

Shared comic book history

Both given similar powers as victims of experimentation by the US government’s Weapon X project, Deadpool and Wolverine share a love-hate relationship.

First appearing as adversaries in the 1980s, by 1999 they were firm “frenemies” in the comics. In one issue, they bonded over their mutual tortures at the hands of the Weapon X programme and even shared a beer. “This was the start of an awkward friendship,” wrote Nerdist’s Eric Diaz.

In 2019, Disney acquired 20th Century Fox – making Deadpool and Wolverine official members of the MCU.

The film realises an ambition years in the making. Jackman insists he “really did mean it” when he declared himself “done” with Wolverine after 2017’s critically-acclaimed Logan, which saw the superhero meet his end.

But weeks after filming wrapped in 2016, he saw the first Deadpool – offering a different twist on the genre in its anarchistic comedy – and regretted his decision.

“For four or five years, all I could see were those characters together,” he explains, imagining classic buddy comedy/drama pairings like 48 Hours or The Odd Couple.

Disney

DisneyEventually, it became an itch he had to scratch. “I can tell you the date. August 14 2022. I was driving and it came to me like that – I wanted to do [Wolverine] again… with Ryan playing Deadpool.”

Pulling over, he rang Reynolds to plead his case. The timing was perfect, because the actor was hours away from pitching a third Deadpool film to Marvel with Levy.

Levy says Jackman’s arrival was key to giving the third film its “why” and its “heart”.

Wolverine’s ‘fresh’ return

For Reynolds’ Deadpool, this means plenty of X-rated jokes at Disney’s expense. For Jackman, it is a golden opportunity to explore new depths of his much-loved Wolverine.

“There’s parts of the character that I’d always pitched in different versions and tried to get across. It was something that I’ve been scratching at. And these guys hit it.”

Jackman, 55, says his renewed enthusiasm may come from the perspective age brings, after years on stage and a starring role in screen musical The Greatest Showman.

“When you come back because you desperately want to, and particularly in this form, it felt incredibly fresh.

“There’s one monologue I get which has more countable words than I’ve [previously] used in an entire movie,” he explains.

The final trailer sent fans into meltdown, with the shock appearance of Dafne Keen returning as an older version of Wolverine’s daughter, Laura, from his famous Logan farewell.

Alamy

Alamy Alamy

AlamyIt is the epitome of fan service. But willpower alone does not make a blockbuster capable of potentially reviving Marvel’s fortunes. That instead relies on authentic, cohesive storytelling.

Deadpool and Wolverine is the only Disney-backed MCU release this year (thanks to delays from the writers’ strikes), but this may not be a bad thing.

Reviews from critics have been mixed, but many have described the film as the shot in the arm that Marvel needs.

The Guardian’s three-star review said the film “mocks the MCU back to life”, with Deadpool “basically right” in his saviour complex quip.

Variety praised Deadpool and Wolverine’s “misty-eyed” fan-service as a “welcome corrective” to 15 years of MCU convolution, even if the special effects and action sequences don’t always match 2018’s sequel. “The entire genre could use a shake-up, and this jester-like character is just the guy to do it,” added Peter Debruge.

However, the Independent’s two-star review could not look past the “tedious and annoying corporate merger of a film”.

The Hollywood Reporter said the film is on course for a massive $165m (£127m) opening weekend in the US, which would mark the biggest R-rated opening of all time.

Can it save the MCU? Not on its own – multiverse content problems run deep. But it’s certainly energised it and is, whisper it, fun – whichever timeline you’re in.