BBC

BBCDelivering safe care continues to be a challenge in every emergency department in Scotland, according to a senior A&E doctor.

As the service gears up for winter, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) is warning that the government’s winter planning is not doing enough to support A&E departments as they approach their busiest time of year.

The Scottish government said it is prioritising investment in front-line services.

The warning comes after the figure for August’s emergency department waiting times was the worst ever recorded for that month, with just under a third of patients waiting longer than four hours to be seen.

The government target that 95% of patients should be admitted, transferred or discharged from an emergency department within four hours has not been met since summer 2021.

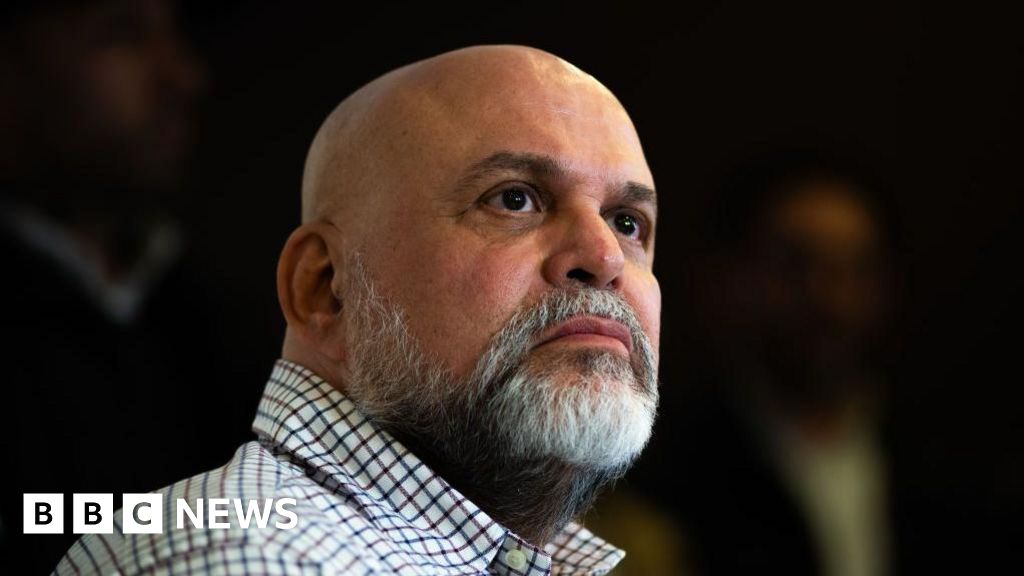

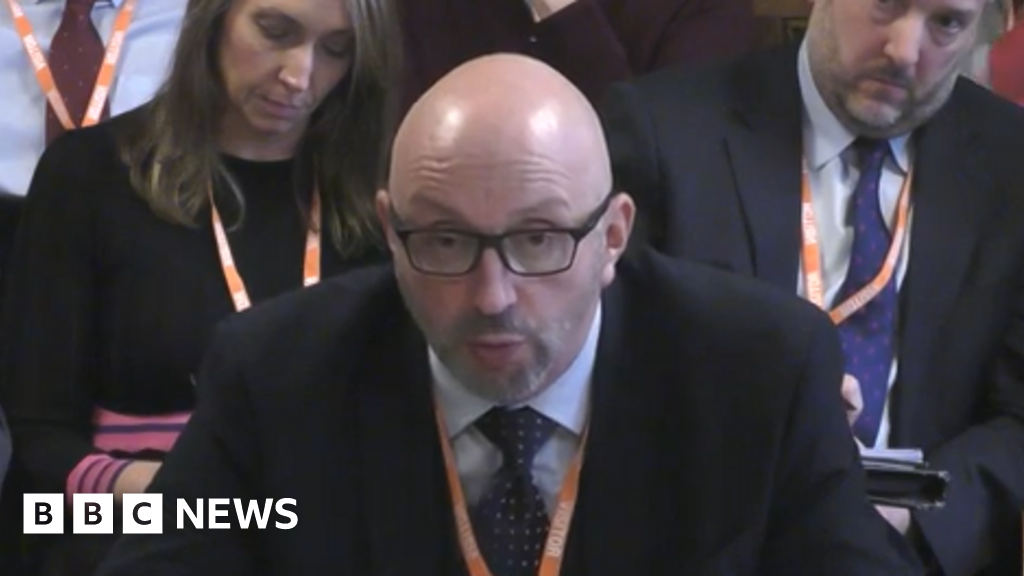

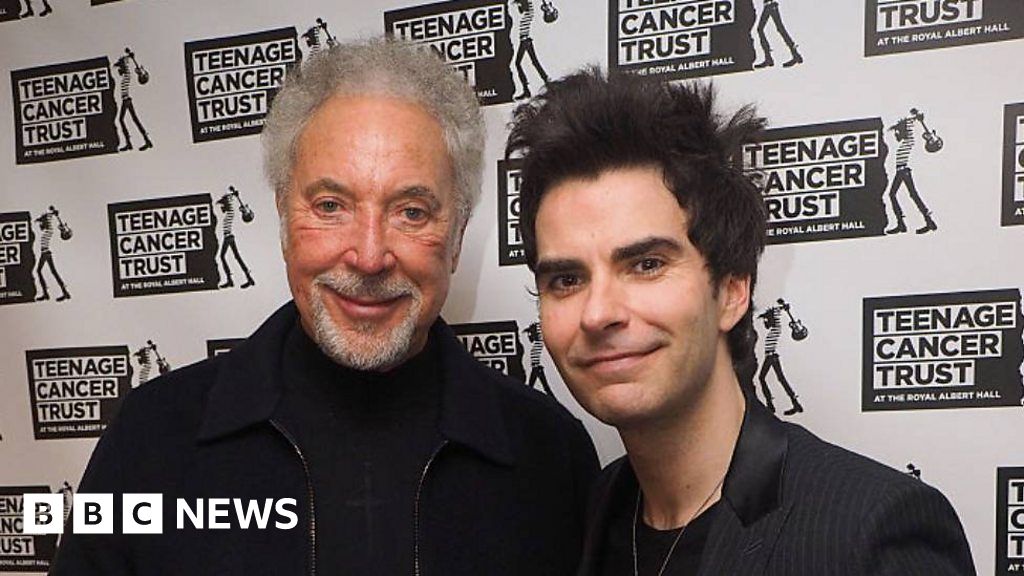

Dr John Paul Loughrey

Dr John Paul LoughreyDr John Paul Loughrey, vice president for Scotland of the RCEM, told BBC Scotland News that the Scottish government’s plans for the NHS this winter would not improve the experience of staff or patients.

He accused the Scottish government of “continuing to disregard” the urgent need to keep patients moving through the hospital system to stop them getting stuck in A&E.

“We are seeing lots of discussion, but we haven’t seen any useful measures so far that will make it any better for people working in A&Es this winter,” he said.

He said there had been no opportunity for A&E departments to “reset” over the summer as they would have traditionally, and that it continued to be a very challenging environment – with fears it would get even worse over the winter.

Dr Loughrey added that every day recently had been like “the winter crisis of winters before, but every day”.

“Sometimes giving safe care can be a challenge in every A&E in Scotland,” he said.

He highlighted that one of the big issues in the emergency department was moving patients out of A&E into specialist beds elsewhere in the hospital.

This, he said, meant it was difficult to treat new patients arriving at A&E – leading to queues of ambulances outside and patients sometimes left in corridors which he said was “inhumane”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr Loughrey said this “chronic pressure” was also leading to burnout for A&E staff, with some choosing to leave emergency medicine.

There were failures in the entire system but a lot of the pressure and risk was being heaped on this one area of emergency medicine, he added.

“We can’t accept that this is the new normal – we know there are solutions to this problem but they are not easy and not cheap.”

He said there had to be an increase in capacity in acute medicine, and hospital occupancy had to come down.

The RCEM carried out a survey of conditions in Scotland’s 21 emergency departments between March and April this year which found that, on average, A&Es were working at 182% capacity.

A total of 12.8% of patients were being treated in corridors because of a lack of available space, with 26.1% of patients stuck in the emergency department because there were no beds available to admit patients into hospital for further treatment.

The college say there has been “chronic” pressure on A&Es over the last two years that shows no sign of letting up as winter approaches.

Its data estimated that hundreds of patients died as a result of long delays in an emergency department last year, with Dr Loughrey warning this situation was likely to be repeated again this winter.

Fuel poverty

Asked about plans to limit winter fuel payments – which was previously paid to all pensioners to help with energy bills, but will now only be made to those who receive certain benefits – Dr Loughrey warned about the impact of deprivation on the most vulnerable in society.

He said: “Every day in A&E [doctors see] people experiencing fuel poverty and food poverty.

“Deprivation is a huge problem and we know that anything that makes life more difficult financially for people will result in unexpected attendances to emergency departments.”

He said patients in the most deprived areas were the biggest users of both primary and emergency care.

“Data was collected in the last two years for the impact on the elderly around about winter and, for example, looking at the number of patients presenting with hypothermia from their own homes.

“We do know that measures that make things more difficult for patients to live a quality life at home will result in more pressures on A&Es.”

He said he worried that this winter could be worse because of some of these factors, and urged the government to address acute capacity issues and also address fuel and food poverty.

Dr Loughrey added: “Patients with mental health problems, the frail, the elderly and the vulnerable are the least able to be able to tolerate those ultra long delays in A&E departments”

Year-round surge planning

Prof Andrew Elder, president of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, said: “As we move closer to another Scottish winter, when pressure on access to and flow through our acute hospital beds will rise substantially, the latest figures on delayed discharges are a source of huge alarm.”

The Scottish government said: “We have moved to year-round surge planning in recognition that surges don’t just occur in winter and can happen at any time of the year.

“Surge planning is now a continual process in which our key partners in statutory services, independent, third and voluntary sectors work collaboratively, including making decisions regarding how funding and resources are deployed.

“We continue to prioritise investment in front-line services in 2024-25 with over £14.2bn investment in our NHS boards with additional funding over half a billion – an almost 3% real terms uplift.”

Last month Health Secretary Neil Gray insisted the NHS in Scotland was not in crisis despite “facing challenge”.