Inside the bodies of humpback whales are clues about how climate change is transforming Antarctica. The BBC’s Victoria Gill and Kate Stephens crossed the Southern Ocean, with the researchers, on a mission to follow and study the giant whales of this remote, frozen wilderness.

At 03:00 in the morning there is an almighty crash. Every drawer in our cabin is flung open and contents hurled against the wall. We hit a 12-metre wave.

I’m not a seafarer; this is alarming, but apparently not unusual on the Drake Passage – the stretch of the notoriously rough Southern Ocean we are on. We’re aboard a 200-passenger tourist ship, with a team of wildlife scientists, on our way to the Antarctic Peninsula.

One of the researchers, Dr Natalia Botero-Acosta has an arresting piece of equipment in her hand luggage – a custom-made crossbow. “It’s not a weapon,” she explains. “It’s a scientific tool we use to collect whale skin and blubber samples.”

Using the crossbow and a drone, the researchers will carry out up-close health checks on every humpback whale they can find, to work out if these massive mammals are getting enough to eat.

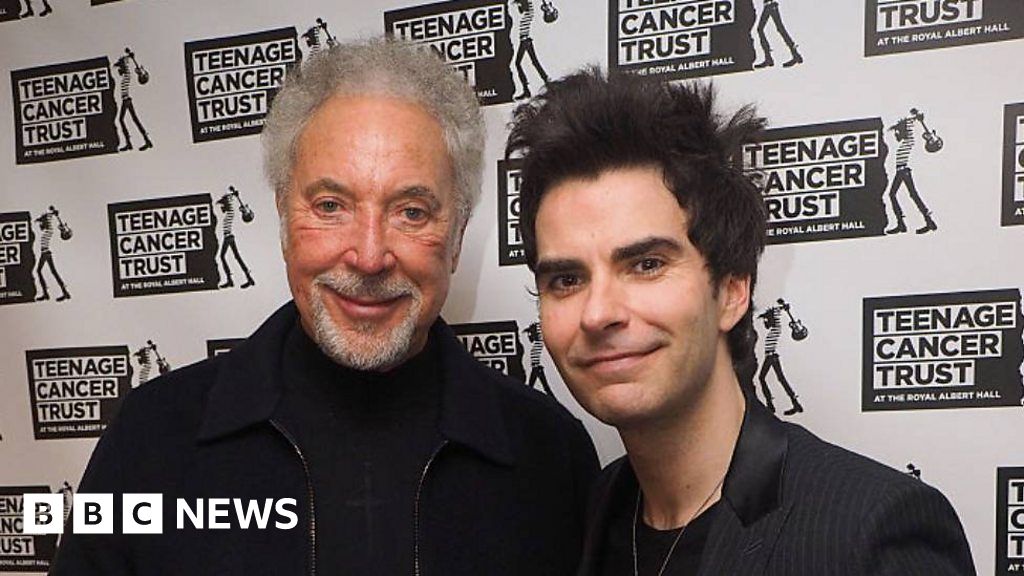

Victoria Gill

Victoria GillIt is an important question – not just for mighty, 40-tonne humpbacks that travel thousands of kilometres to gorge themselves in the cold seas – but for the health of the ocean and our planet.

In the rich, freezing seas off the peninsula, penguins, seals and many whales feed on Antarctic krill.

These diminutive, almost unimaginably numerous, shrimp-like creatures thrive under sea ice. As the climate warms up, scientists are racing to understand what that means for this ice-dependent food supply.

Australian Antarctic Division

Australian Antarctic DivisionEarly on our first Antarctic morning, in mercifully calm coastal waters, we set out on a small, inflatable boat called a zodiac.

Cloud is descending and it is starting to snow. Leading our Antarctic whale research mission is Chris Johnson, who is the wildlife charity WWF’s global expert on whale conservation.

In conditions like this,” says Chris, “the best way to find whales is to listen – we’ll switch off the zodiac engine and close our eyes.”

The silence is transformational. Multiple, overlapping blows of whale exhalations echo off mountains that rise vertically out of glassy water. Gigantic, hungry humpbacks are feeding in this bay. All around our small boat, animals are breathing, then diving – opening their cavernous mouths to let krill-laden seawater rush in.

We head slowly in the direction of the nearest blows and Natalia reaches for her crossbow.

The giant mammals build up chemical clues about their environment in their blubber – clues that Natalia plans to collect.

Paul Fahy/WWF

Paul Fahy/WWFShe picks up one of the crossbow bolts. On the business end, there is a 3cm metal tip that plucks a piece of skin and blubber from the whale’s body. A rubber stopper prevents the bolt from penetrating further: It grabs a sample, then bounces off the animal and floats in the water.

“It’s 3cm from an animal that’s 14m long – so it’s like a mosquito bite,” says Natalia. Sure enough, when her bolt takes a nick out of the body of a huge, female whale, the animal doesn’t flinch.

It’s a mother, side-by-side with her calf. She seems intrigued – circling our boat slowly, then gliding directly underneath. Her giant head and white pectoral fins – fringed with barnacles – are visible as she slowly floats beneath us.

“Hold on in case she comes up,” says Chris. But mother whale glides on, surfacing on the other side of us with a blow.

Victoria Gill

Victoria GillThe calf is even more curious, raising its head out of the water. The young marine mammal seems to examine us; we’re a strange group of tiny, terrestrial mammals in a small, rubber boat. I can’t stop myself greeting the calf: “Hello, beautiful.”

Baby humpbacks spend a year nursing on their mothers’ rich milk. With a hungry, one-tonne newborn, calories are important.

“We need to find the most critical feeding habitats for whales, so we can protect them,” explains Chris.

The health of whales, he explains, shines a light on the health of the whole Antarctic ecosystem. And whales are physically necessary for a healthy ocean: Humpbacks eat krill, and krill eat microscopic plants that live in sea ice – plants that absorb planet-warming carbon as they grow. Whales then poop (in vast quantities) and fertilise the marine plants.

It’s a virtuous, productive cycle that climate change is disrupting. “These are natural processes we rely on for fresh air, food and clean water,” says Chris. “Places like this are important for all of us.”

Victoria Gill

Victoria GillThere is a group of humpbacks in this bay and Natalia sets up to take another biopsy. She seems in sync with the whale. When it arches its back above the surface, that’s the moment – and the ideal, blubber-rich area – for her to aim for. There’s a gentle “thunk” as the bolt bounces off the whale, taking its nugget of tissue.

Back in her lab at the University of California Santa Cruz, Natalia will be able to tell if this whale was hungry, stressed or pregnant from chemical signals, or hormones, that build up in its blubber.

“Pregnancy data is so valuable,’ Natalia says. “My colleague previously found that, in years when there is low sea ice, you have lower pregnancy rates. [We’re really seeing] the effect of climate change – and all these conservation threats – on the animals.”

Most mature humpbacks here will eat about three million Antarctic krill each day, as they bulk up for a 8,000km journey back to breeding grounds in the tropical Pacific.

Chris Johnson/WWF/UCSC Research under NOAA Permit

Chris Johnson/WWF/UCSC Research under NOAA PermitWhile a single krill is just 6cm long fully-gown, collectively they weigh about 400 million tonnes. That is similar to the combined weight of every human on Earth. The swarms of krill here depend on sea ice – they graze on its algae and survive in its crevices.

Marine ecologist Prof Angus Atkinson from Plymouth Marine Laboratory says climate change is a threat to krill. “Since 2017, there has been a worrying decline in Antarctic sea ice,” he says. In 2023, it reached a record low, with over 2 million sq km less ice than usual during winter.

Another way the team is studying the whales here is from above – with a drone. The remotely controlled aerial cameras mean scientists can record spectacular displays of behaviour that can’t be seen from the surface.

Chris launches his drone and we watch a group of humpbacks perform a perfect demonstration of bubble net feeding. Working together, they blow bubbles in a spiral, trapping the krill swarm. Like colossal, synchronised swimmers, they lunge through the middle of the bubble net open-mouthed.

Chris Johnson/WWF/UCSC/Research under NOAA Permit

Chris Johnson/WWF/UCSC/Research under NOAA PermitOne whale creates a solo bubble net, then sweeps krill into its mouth with a huge fin. “It’s using its pectoral fin as a tool,” says Chris.

The drone doesn’t just provide a spectacular view – it’s used to weigh the whales. Chris explains: “We measure the length and width of their bodies to work out how fat they’re getting during the season.”

Scientists have seen evidence of whales “getting skinny” because of a climate-linked food shortages. One study of Southern right whales – that feed on krill, then migrate to the South African coast to give birth – showed that the animals are 20% thinner compared to 30 years ago.

Krill are difficult to count and it isn’t clear if numbers are declining, but research has shown that the population is moving south into colder water. A regular check on humpbacks’ weight will provide more clues.

Krill biologist Prof So Kawaguchi from the Australian Antarctic Division says it’s vital to understand the whole life cycle and the behaviour of krill. “If climate change affects the behaviour and distribution of the swarms, some predators are going to suffer,” he says. “Krill could move out of their reach.”

Paul Fahy/WWF

Paul Fahy/WWFWhales shrinking is an indicator of poor health, explains Chris. “There are multiple causes – climate change, fisheries, ship strikes and underwater noise pollution – it’s all adding up.”

There is a krill fishery in the Southern Ocean. The oil is used in to make some animal feeds and supplements. Strict catch limits are designed to protect Antarctic wildlife, but the WWF wants some areas designated no fishing zones to protect whales’ food supply. “We’re advocating closing off really sensitive wildlife feeding habitats,” Chris explains.

As Chris looks intently at his drone display, he suddenly calls out: “Mom’s pooping!”

The aerial view shows a female humpback relaxing near our boat, right next to a large volume of floating faeces. Biologist Sarah Kienle grabs a large sample jar from the kit bag and leans over the side to scoop some up.

The waste has the aroma of highly concentrated rotting fish, but Sarah is delighted. “Whale poop is so hard to find and it contains all this information about what they’re eating. We can even get DNA and hormones from it. It’s liquid, smelly gold!”

Paul Fahy/WWF

Paul Fahy/WWFBack aboard the ship, the team use a store room as a makeshift laboratory. At a small table, Natalia and Sarah take each sample from its arrow-tip casing and put it in a sealed tube to be transported back to Natalia’s lab.

On the ship, the samples go into a freezer. On the long journey home though, Natalia travels with her samples tucked into a small, insulated picnic box. She often asks cabin crew on a flight for ice from the drinks cart to ensure her precious samples are kept as cold as possible.

While working from a tourist ship has its limitations, it means the team can work in several sites around the peninsula. “Scientists and the tourists want to get to the same places – hotspots of biodiversity and animals,” explains Sarah, who has joined the team from Baylor University in Texas.

The tour company, Intrepid, provides space and facilities for the scientists. For the team, Chris says, being on the ship means access to one of the most remote places on Earth.

Elly Gearing

Elly GearingTourism can leave its mark. The number of people who make the trip to Antarctica for a holiday has increased dramatically in recent years. In the season between 2022 and 2023, a record 104,000 people visited. Before the 1980s, just a few hundred people came each year.

Antarctic adventures have a high carbon footprint, and any visitor – scientist, tourist or journalist – could unwittingly bring in seeds or microbes that do not belong on clothes or boots. Expedition guides on this trip actually vacuum out passengers’ backpacks and pockets to help prevent that. Bobbles on hats are discouraged when ashore – they can shed fibres.

But there is evidence that experiencing the frozen continent in person can inspire visitors to advocate for its protection.

Working in this way also means researchers operate on the tourist ship’s schedule, with just four full days travelling around the Peninsula before heading back across the infamous Drake Passage.

Elly Gearing

Elly GearingOn the last day, two whales the team are following suddenly stop next to an iceberg and stop moving. “They’ve fallen asleep,” explains Natalia.

Natalia approaches every animal with care. And she has the best chance to get a good sample from a moving whale – as it arches out of the water. “I’m going to put a bolt in the water, just to make a splash and see if it will wake them up,” she explains.

Thunk.

Splash.

Nothing.

“They didn’t move,” she smiles. “No reaction whatsoever. They’re very sleepy.”

Finally, the two whales stir and Natalia takes her final shot to get one last, precious sample containing information about what is happening to this environment and the wildlife that depends on it.

This is a place that humanity depends on too – a productive, icy ocean that helps cool our planet. Working out exactly how it is changing means monitoring it.

So the scientists hope to return to this frozen wilderness next summer to keep up their regular health check in on its largest inhabitants.

Victoria Gill

Victoria Gill