Business reporter & political correspondent BBC news

BBC

BBCPressure has increased on the chancellor’s tax and spending plans after a surplus in government finances missed official forecasts.

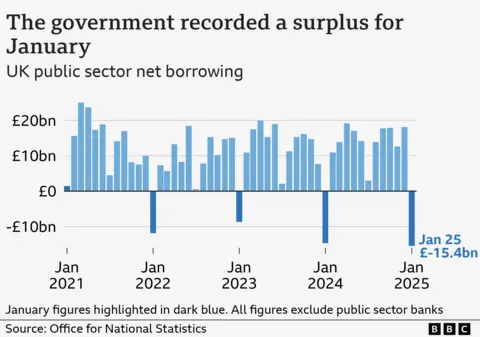

The surplus – the difference between what the government spends and the tax it takes in – was £15.4bn in January, the highest level for the month since records began more than three decades ago.

But the figure was much lower than the £20.5bn predicted by the UK’s official forecaster, re-igniting speculation that Rachel Reeves will either have to cut public spending or raise taxes further next month to meet her self-imposed rules for the economy.

The government reiterated on Friday that its so-called fiscal rules were “non-negotiable”.

On 26 March, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) will release its latest outlook for the UK economy and public finances and will detail what headroom the chancellor has. At the same time, Reeves will announce her Spring Forecast.

Last October, the watchdog said she had £9.9bn in headroom to meet her rules following her first Budget.

However, weak economic growth and higher borrowing costs have weighed on that wriggle room.

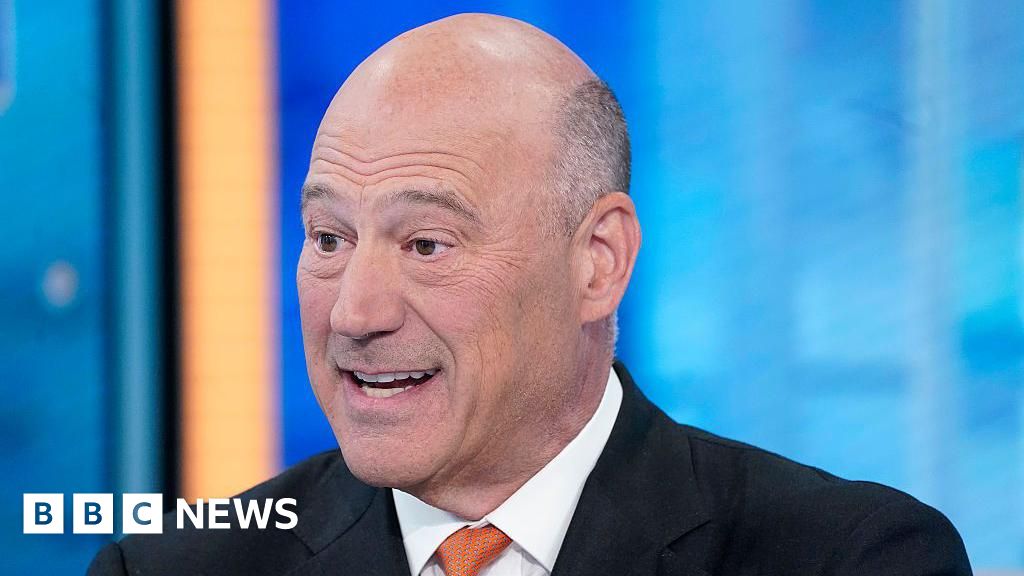

“In order to meet her fiscal rules, the chancellor will need to raise taxes and/or cut spending,” said Alex Kerr, UK economist at Capital Economics, who added that the headroom had been “wiped out”.

He said Reeves’s options ahead of her Spring Forecast were already “bleak” before the “ratcheting up of pressure on European governments to increase defence spending” amid uncertainty over the outcome of the war in Ukraine.

Government departments will submit line-by-line breakdowns of their spending, along with suggestions for where savings could be made, to the Treasury in the coming days.

Fiscal rules are self-imposed by most governments in wealthy nations and are designed to maintain credibility with financial markets.

The chancellor has two main rules which she has argued will bring stability to the UK economy: day-to-day government costs will be paid for by tax income, rather than borrowing and to get debt falling as a share of national income by the end of this parliament in 2029/30.

However, there has been speculation that if Reeves wants to avoid breaking her own rules, cuts in public spending or further tax rises could be announced.

Cara Pacitti, senior economist at the Resolution Foundation think tank, said recent economic data “could leave the chancellor in the unenviable position of needing to raise taxes or cut spending to meet her fiscal rules”.

Latest figures revealed UK economic growth has been anaemic, and inflation – which measures the rate that prices go up by – has risen, putting pressure on household budgets. The chancellor has previously ruled out borrowing more or raising taxes again, which points to spending cuts.

Following the government finance figures, Darren Jones, chief secretary to the Treasury, reiterated that the government’s fiscal rules were “non-negotiable”

Shadow chancellor Mel Stride said the figures “expose the true cost of Labour’s reckless economic policies”.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) cautioned that government revenue figures from a single month are likely to be revised and do not meaningfully affect the overall fiscal outlook.

But the independent think tank added the figures showed much more borrowing in January than was planned last March.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said borrowing in the financial year to January 2025 was £118.2bn, some £11.6bn more than at the same point in the last year.

Isabel Stockton, senior research economist at the IFS, said: “This extra borrowing in the short term is coupled with the promise of fiscal restraint in future, but it remains to be seen whether this will be enough to meet her ‘non-negotiable’ fiscal rules without further tax rises or even tighter spending plans.

“If – and it is still very much an if – the forecast moves against the chancellor, she’ll face a truly unenviable set of choices, none of which are made easier by the upwards pressures on defence spending.”

The government tends to take more in tax than it spends in January compared with other times of the year due to the amount it receives in self-assessed taxes in the month.

Despite last month’s £15.4bn being a record figure for a surplus, it undershot forecasts due to lower-than-expected tax receipts, suggesting weakness in the UK economy.

Spending on public services, benefits and debt interest were all higher than last year, the ONS added.

Liz Martins, senior UK economist at HSBC, told the BBC’s Today Programme the higher borrowing was a “little bit worrying”, adding “if we’re off track now the OBR might judge that that’s going to persist”.

She added if the watchdog thought borrowing would remain elevated “then the government might need to make further changes” on its spending and taxation policies.

Separate figures from the ONS showed retail sales in the UK rebounded in January, largely due to strong food sales.

But clothing shops and household goods reported “lacklustre sales due to weak consumer confidence”, according to ONS senior statistician Hannah Finselbach.

She said sales in shops had fallen over the past three months, and were below pre-Covid levels.