BBC Burmese

BBC BurmeseMandalay used to be known as the city of gold, dotted by glittering pagodas and Buddhist burial mounds, but the air in Myanmar’s former royal capital now reeks of dead bodies.

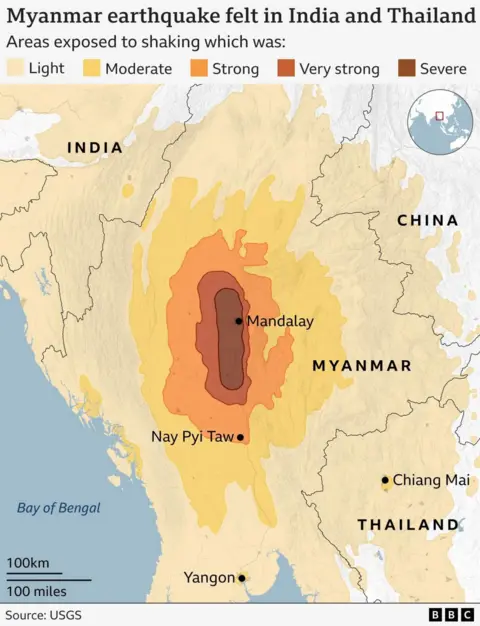

So many corpses have piled up since a 7.7 magnitude earthquake struck last Friday close to Mandalay, that they have had to be “cremated in stacks”, one resident says.

The death toll from the quake and a series of aftershocks has climbed past 2,700, with 4,521 injured and hundreds still missing, Myanmar’s military chief said. Those figures are expected to rise.

Residents in the country’s second most populous city say they have spent sleepless nights wandering the streets in despair as food and water supplies dwindle.

The Mandalay resident who spoke of bodies being “cremated in stacks” lost her aunt in the quake.

“But her body was only pulled out of the rubble two days later, on 30 March,” said the 23-year-old student who wanted only to be known as J.

Poor infrastructure and a patchwork of civil conflicts are severely hampering the relief effort in Myanmar, where the military has a history of suppressing the scale of national disasters. The death toll is expected to keep rising as rescuers gain access to more collapsed buildings and cut-off districts.

J, who lives in Mandalay’s Mahaaungmyay district, has felt “dizzy from being deprived of sleep”, she said.

Many residents have been living out of tents – or nothing – along the streets, fearing that what’s left of their homes will not hold up against the aftershocks.

“I have seen many people, myself included, crouching over and crying out loud on the streets,” J said.

But survivors are still being found in the city. The fire service said it had rescued 403 people in Mandalay in the past four days, and recovered 259 bodies. The true number of casualties is thought to be much higher than the official version.

In a televised speech on Tuesday, military chief Min Aung Hlaing said the death toll may exceed 3,000, but the US Geological Survey said on Friday “a death toll over 10,000 is a strong possibility” based on the location and size of the quake.

Young children have been especially traumatised in the disaster.

A local pastor told the BBC his eight-year-old son had burst into tears all of a sudden several times in the last few days, after witnessing parts of his neighbourhood buried under rubble in an instant.

“He was in the bedroom upstairs when the earthquake struck, and my wife was attending to his younger sister, so some debris had fallen onto him,” says Ruate, who only gave his first name.

“Yesterday we saw bodies being brought out of collapsed buildings in our neighbourhood,” said Ruate, who lives in the Pyigyitagon area.

“It’s very sobering. Myanmar has been hit by so many disasters, some natural, some human made. Everyone’s just gotten so tired. We are feeling hopeless and helpless.”

A monk who lives near the Sky Villa condominium, one of the worst-hit buildings reduced from 12 to six storeys by the earthquake, told the BBC that while some people had been pulled out alive, “only dead bodies have been recovered” in the past 24 hours.

“I hope this will be over soon. There are many [bodies] still inside, I think more than a hundred,” he said.

Crematoriums close to Mandalay have been overwhelmed, while authorities have been running out of body bags, among other supplies, including food and drinking water.

Around the city, the remains of crushed pagodas and golden spires line the streets. While Mandalay used to be a major centre for the production of gold leaf and a popular tourist destination, poverty in the city has soared in recent years, as with elsewhere in Myanmar (formerly called Burma).

BBC Burmese

BBC BurmeseLast week’s earthquake also affected Thailand and China, but its impact has been especially devastating in Myanmar, which has been ravaged by a bloody civil war, a crippled economy and widespread disillusionment since the military took power in a coup in 2021.

On Tuesday, Myanmar held a minute of silence to remember victims, part of a week of national mourning. The junta called for flags to fly at half mast, media broadcasts to be halted and asked people to pay their respects.

Even before the quake, more than 3.5 million people had been displaced within the country.

Thousands more, many of them young people, have fled abroad to avoid forced conscription – this means there are fewer people to help with relief work, and the subsequent rebuilding of the country.

Russia and China, which have helped prop up Myanmar’s military regime, are among countries that have sent aid and specialist support.

But relief has been slow, J said.

“[The rescue teams] have been working non-stop for four days and I think they are a little tired. They need some rest as well.

“But because the damage has been so extensive, we have limited resources here, it is simply hard for the relief workers to manage such massive destruction efficiently,” she said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile the junta had said that all assistance is welcome, some humanitarian workers have reported challenges accessing quake-stricken areas.

Local media in Sagaing, the earthquake’s epicentre, have reported restrictions imposed by military authorities that require organisations to submit lists of volunteers and items that they want to bring into the area.

Several rights groups, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have urged the junta to allow aid workers immediate access to these areas.

“Myanmar’s military junta still invokes fear, even in the wake of a horrific natural disaster that killed and injured thousands,” said Bryony Lau, Human Rights Watch’s deputy Asia director.

“The junta needs to break from its appalling past practice and ensure that humanitarian aid quickly reaches those whose lives are at risk in earthquake-affected areas,” she said.

The junta has also drawn criticism for continuing to open fire on villages even as the country reels from the disaster.