Getty Images

Getty ImagesA mum opens the door to two plain-clothes police officers in Hackney, east London.

They’re here to talk to her son. She’s “terrified”.

Normally a knock on the door like this is bad news, say PCs Jovon Lennon and Dean Waters.

But they’re not here to arrest anyone.

The house is one of five stops on their daily rounds, calling in on young people the police believe are at risk of being drawn into crime.

“It’s very rare that police are coming to young people’s doors like this and not trying to collect them to put them in a cell,” says PC Lennon.

The officers are from Hackney’s Integrated Gangs Unit which was set up to build better relationships with the community and deter people from gangs.

BBC Newsbeat was given exclusive access by the Metropolitan Police to join them at work. They asked not to be photographed while on duty.

When the boy’s mum realises why they wanted to speak to her son, the mood changes.

“She was initially a bit thrown off because she thought we were there to deliver bad news,” says PC Lennon.

“We’re literally just here to keep them on the right track.”

That support could just be a warning of what could happen if they get sucked into crime but it can also include help getting a job or on a course.

In serious circumstances, it can even mean getting help to leave the area if someone feels unsafe.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHackney has one of the capital’s worst rates of gang and knife violence with more than 350 knife crime offences already recorded so far this year.

But it’s not just a London problem. According to government data, just over 40% of murders in England and Wales last year were knife-related.

Recorded knife crime remains lower than it was before the Covid-19 pandemic but is still higher than it was in 2012 when numbers began to gradually increase.

A top police officer in the Met, Det Ch Supt James Conway, tells Newsbeat these types of crime are an “area of focus” for the force.

Neighbourhood operations like the one carried out by PCs Lennon and Waters are part of a plan to reduce knife crime.

But with stretched resources it can be a challenge to keep on top of it.

In 2023, a review into the Met by Baroness Casey found that the force “no longer has a functioning neighbourhood policing service”.

“Sadly there’s not enough of us,” says PC Lennon.

“Sometimes we get taken away from what we do to assist with other stuff.”

Det Ch Supt Conway admits officers have to be directed away from community duties to deal with other events.

The riots earlier this summer are one example, he says, and can be a “real challenge” for local policing efforts.

He acknowledges there’s still room for improvement but insists his officers in Hackney have “made big strides” over the past year.

‘It’s normal now’

At some of the houses PCs Lennon and Waters visit, the people they’re here to talk to have already been pulled into gangs. Three of them routinely carry knives.

“It’s sad because it gets to the point where it’s normal now,” says PC Lennon.

“You’re not even shocked any more.”

Rates of knife crime in Hackney have stayed steady over the past five years, but Det Ch Supt Conway says police have noticed a change in how gangs get young people into crime.

“The degree of exploitation of young people by criminal gangs feels a lot more serious now,” he says.

“We’ve seen attacks, we’ve seen violence come about because of what people are posting on social media and the way they’re using social media to call on attacks on rivals.”

PA Media

PA MediaHe says there’s lots of complicated reasons why people might get drawn in.

“Poverty, deprivation, lack of opportunity – they all contribute,” he says.

Det Ch Supt Conway says gangs prey on this, offering money, designer clothes and trainers to groom young people.

But those luxury items quickly become a debt that needs to be repaid, he says.

“This is not a route to riches,” he says. “This is a route to control and to exploitation.”

While he says police can’t solve the root causes, he believes officers like PC Lennon and PC Waters can show young people an alternative path.

The officers try to build a relationship with the community, and don’t wear uniforms.

They insist on meeting vulnerable people face-to-face where they can.

Returning to that knock on the door scenario, PC Lennon says the police don’t usually visit for a conversation.

“But with this, you’re in a situation where there’s no impending situations,” he says.

“We want it to stay like that.”

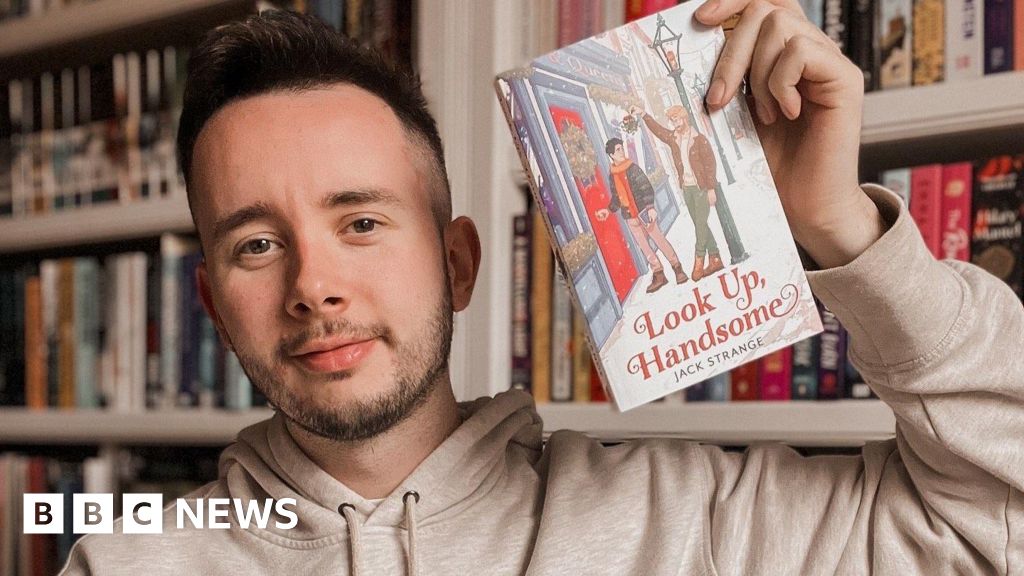

One of the unit’s regular visits is to the Morningside Community Youth Club.

Volunteer Kevin says they often have a kick-about and even once brought police horses to meet members.

“Once we build that rapport with the police, I reckon we can gain a mutual understanding of what we both want,” he says.

Det Ch Supt Conway says it’s important work but to make a real difference to cutting knife crime and gang violence, “we need to work in partnership with government, with local authorities, with housing, with schools, with education, with employers”.

Youth clubs across England have faced a significant cut in funding, with the YMCA reporting more than half the country’s centres have closed since 2010. In London alone, the Mayor’s office says 130 have closed.

Lib Peck, the Director of London’s Violence Reduction Unit, told Newsbeat the approach of the city’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, was “to be tough on violence… at the same time as being tough on the complex causes of violence”.

She said thousands of initiatives were being supported including funding youth workers in police custody and hospitals as well as spending £15.6m “to help rescue young people who are being exploited by criminal gangs”.

On a national level, a Home Office spokesperson told Newsbeat the government was committed to supporting youth services across the country.

On Monday, it announced a new anti-knife crime coalition as part of its pledge to protect people from getting sucked into gangs.

Measures include banning zombie knives and machetes, with thousands already being surrendered.

The department also told Newsbeat it was rolling out a Youth Futures programme which it says will “bring local services together to deliver support for young people in their communities and help to tackle youth violence”.