“Can I give you some polar bear advice?” asks Tee, a confident 13-year-old we meet during a visit to a high school in Churchill, Canada.

“If there’s a bear this close to you,” she says as she measures a distance of about 30cm with her hands, “make a fist – and punch it in the nose.

“Polar bears have very sensitive noses – it’ll just run away.”

Tee has not had to put this advice to the test. But growing up here – alongside the planet’s largest land predator – means bear safety is part of everyday life.

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCSigns – in shops and cafes – remind anyone heading outside to be “bear aware”. My favourite reads: “If a polar bear attacks you must fight back.”

Running away from a charging polar bear is – perhaps counterintuitively – dangerous. A bear’s instinct is to chase prey and polar bears can run at 25mph (40kmph).

Key advice: Be vigilant and aware of your surroundings. Don’t walk alone at night.

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCChurchill is known as the polar bear capital of the world. Every year, the Hudson Bay – on the western edge of which the town is perched – thaws, and forces the bears on shore. As the freeze sets in in Autumn, hundreds of bears gather here, waiting.

“We have freshwater rivers flowing into the area and cold water coming in from the Arctic,” explains Alyssa McCall from Polar Bears International (PBI). “So freeze-up happens here first.

“For polar bears, sea ice is a big dinner plate – it’s access to their main prey, seals. They’re probably excited for a big meal of seal blubber – they haven’t been eating much all summer on land.”

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCThere are 20 known sub-populations of polar bears across the Arctic. This is one of the most southerly and best studied.

“They’re our fat, white, hairy canaries in the coal mine,” Alyssa explains. “We had about 1,200 polar bears here in the 1980s and we’ve lost almost half of them.”

The decline is tied to the amount of time the bay is now ice-free, a period that is getting longer as the climate warms. No sea ice means no frozen seal-hunting platform.

“Bears here are now on land about a month longer than their grandparents were,” explains Alyssa. “That puts pressure on mothers. [With less food] it’s harder to stay pregnant and to sustain those babies.”

While their long-term survival is precarious, the bears draw conservation scientists and thousands of tourists to Churchill every year.

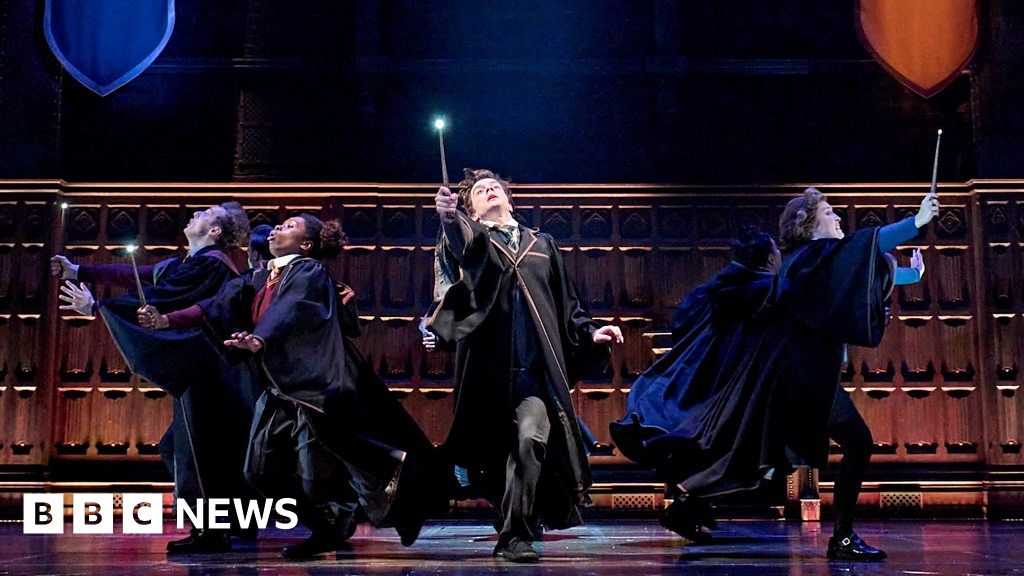

We tag along with a group from PBI to search for bears on the sub-Arctic tundra – just a few miles from town. The team travels in a tundra buggy, a type of off-road bus with huge tyres.

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBCAfter a few distant sightings, we have a heart-stopping close encounter. A young bear approaches and investigates our slow two-buggy convoy. He sidles up, sniffs one of the vehicles, then jumps up and plants two giant paws up on the side of the buggy.

The bear casually slumps back down onto all fours, then looks up and gazes at me briefly. It is deeply confusing to look into the face of an animal that is simultaneously adorable and potentially deadly.

“You could see him sniffing and even licking the vehicle – using all his senses to investigate,” says PBI’s Geoff York, who has worked in the Arctic for more than three decades.

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBCBeing here in ‘bear season’ means Geoff and his colleagues can test new technologies to detect bears and protect people. The PBI team is currently fine-tuning a radar-based system dubbed ‘bear-dar’.

The experimental rig – a tall antenna with detectors scanning 360 degrees – is installed on the roof of a lodge in the middle of the tundra, near Churchill.

“It has artificial intelligence, so here we can basically teach it what a polar bear is,” Geoff explains. “This works 24/7, it can see at night and in poor visibility.”

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBC Annie Edwards

Annie EdwardsProtecting the community is the task of the polar bear alert team – trained rangers who patrol Churchill every day.

We ride along with ranger Ian Van Nest, who is looking for a stubborn bear that he and his colleagues tried to chase away earlier that day. “It turned around and came back [towards] Churchill. He doesn’t seem interested in going away.”

For bears that are intent on hanging around town, the team can use a live trap: A tube-shaped container, baited with seal meat, with a door that the bear triggers when it climbs inside.

“Then we put them in the holding facility,” Ian explains. Bears are held for 30 days, a period set to teach a bear that it is a negative thing to come to town looking for food, but that doesn’t put the animal’s health at risk.

They are then moved – either on the back of a trailer or occasionally air-lifted by helicopter – and released further along the bay, away from people.

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCCyril Fredlund, who works at Churchill’s new scientific observatory, remembers the last time a person was killed by a polar bear in Churchill, in 1983.

“It was right in town,” he says. “The man was homeless and was in an abandoned building at night. There was a young bear in there too – it took him down with its paw, like he was a seal.”

People came to help, Cyril recalls, but they couldn’t get the bear away from the man. “It was like it was guarding its meal.”

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCThe polar bear alert program was set up around that time. No-one has been killed by a polar bear here since.

Cyril is now a technician at the new Churchill Marine Observatory (CMO). Part of its remit is to understand exactly how this environment will respond to climate change.

Under its retractable roof are two giant pools filled with water pumped in directly from the Hudson Bay.

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBC“We can do all kinds of controlled experimental studies looking into changes in the Arctic,” says Prof Feiyue Wang.

One implication of a less icy Hudson Bay is a longer operating season for the port, which is currently closed for nine months of the year. A longer season during which the bay thaws and becomes open water could mean more ships coming in and out of Churchill.

Studies at the observatory are setting out to improve the accuracy of the sea ice forecast. Research will also examine the risks associated with expanding the port. One of the first investigations is an experimental oil spill. Scientists plan to release oil into one of the pools, test clean-up techniques and measure how quickly the oil degrades in the cold water.

For Churchill’s mayor, Mike Spence, understanding how to plan for the future, particularly when it comes to shipping goods in and out of Churchill, is vital for the town’s future in a warming world.

“We’re already looking into extending the season,” he says, gesturing towards the port, which has ceased operating for the winter. “In ten years’ time, this will be bustling.”

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCClimate change poses a challenge for the polar bear capital of the world, but the mayor is optimistic. “We have a great town,” he says, “a wonderful community. And the summer season – [when people come to see the Beluga whales in the bay] – is growing.”

“We’re all being challenged by climate change,” he adds. “Does that mean you stop existing? No – you adapt. You work out how to take advantage of it.”

While Mike Spence says “the future is bright” for Churchill, it might not be so bright for the polar bears.

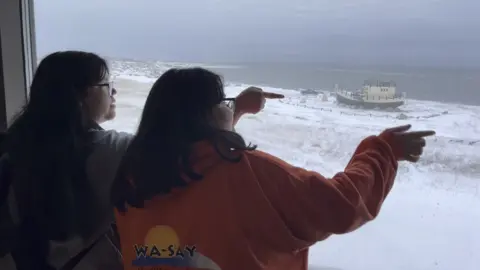

Tee and her friends look out over the bay, from a window at the back of the school building. The polar bear alert team’s vehicles are gathering outside, trying to move a bear away from town.

“If climate change continues,” muses Tee’s classmate Charlie, “the polar bears might just stop coming here.”

The teacher approaches to make sure the children have someone coming to pick them up – that they’re not walking home alone. All part of the daily routine in the polar bear capital of the world.

Kate Stephens/BBC

Kate Stephens/BBC