By Barry O’Connor, BBC News NI

BBC

BBCIt is 75 years since the Northern Ireland football community was rocked to its foundation.

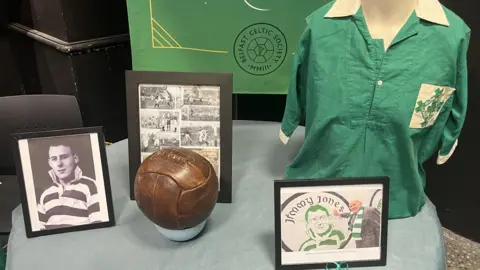

One of local football’s most successful clubs – 14-time league winners Belfast Celtic – folded.

It came months after a shocking incident in which the club’s star striker Jimmy Jones was attacked by Linfield fans after an ugly Boxing Day derby game.

He almost lost his leg after having it stamped on repeatedly by what was described as a “savage mob”.

The attack led to the club leaving the league for good at the end of the season – a decision that would affect west Belfast to this day.

“A vacuum was created instantly,” said Charlie Tully Jr, the president of the Belfast Celtic Society. “75 years on it has never been filled.”

For Charlie and many others, the club is gone but not forgotten. His association with Belfast Celtic goes back via his father, Charlie Tully Sr, who played for both the club and Glasgow Celtic.

“There was a saying at the time – when we had nothing, we had Belfast Celtic,” he said.

“It was more than a football team, it was an integral part of the community. It brought people together, something to lift people when there was unemployment, illness, poverty.

“It was a beacon.”

Why did Belfast Celtic fold?

Belfast Celtic Society

Belfast Celtic SocietyBelfast Celtic had left league football before, in 1920, due to the political instability on the island of Ireland – the Irish War of Independence was ongoing and soon there would be partition and the creation of Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State.

The club – traditionally supported by Catholic and nationalist people in west Belfast – was caught in the crossfire.

“There was rife sectarianism at the time.” said Charlie Tully Jr. “Belfast Celtic unfortunately were targeted by rival fans and decided it was not safe to continue in football and went out of it.”

The club returned in 1924 and set off on an incredible run of success – by 1949, they were the reigning Irish League champions and had won 11 league titles in 16 seasons.

Belfast Celtic Society

Belfast Celtic SocietyLinfield, the only team more successful than Belfast Celtic, was the club’s great rival. The Blues were from the other side of a sectarian divide, being a traditionally Protestant team. Only half a mile separated Windsor Park, Linfield’s home, and Celtic Park.

Games between the two were always feisty affairs – but the derby of Boxing Day 1948 descended into complete chaos.

There was already tension in the build-up. Several weeks before, Linfield lost 2-1 in a bad-tempered cup tie. And then there was Belfast Celtic star Jimmy Jones.

The striker was a former Linfield player who loved to score against his former club, having bagged six in three meetings.

The Boxing Day game was typically bloody – injuries, goals and two red cards. When Linfield scored a last-minute equaliser, fans spilled onto the pitch and some went after Jones.

He was chased onto the terracing under Windsor Park’s South Stand, where his right leg was stamped on and smashed to bits. He almost needed an amputation.

Linfield were punished by having to play two games away from home. No arrests were made. The lack of action left the Grand Old Team’s board of directors with a decision to make.

On 21 April 1949, after a 4-3 win against Cliftonville, a letter of resignation was posted to the Irish League. Belfast Celtic would leave at the end of the season.

The club finished up with a tour of North America, beating Scotland 2-0 in New York. The win is considered one of the greatest in the club’s history.

When they returned from the States on 21 June, club chairman Austin Donnelly made it official, saying: “We have gone from the Irish League.”

For Charlie Tully Jr, the decision – made without consulting fans – left a void in west Belfast.

“Imagine today Glasgow Celtic, Man United, Man City, Liverpool suddenly saying we are not going to play next season – it would have been a similar impact to that.

“Who do these supporters turn their allegiance to? What do these people do on a Saturday?”

For Charlie, Belfast Celtic’s demise “created the allegiance of a lot of fans going from Belfast to Glasgow to support Celtic” as well as other English teams.

“The community, the businesses were affected, the spirit – they felt Belfast Celtic belonged to them. That bond is unique.”

Why did Belfast Celtic not return?

The club would play a handful of friendlies over the years, including against Glasgow Celtic in 1952. Their last game, a testimonial match against Coleraine, came in 1960.

But a return to league football never happened.

When the club’s ground made way for a new shopping centre, the Park Centre, in 1985, it ended any hope of a comeback, said Charlie Tully Jr.

Some clubs have carried the name forward – Belfast Celtic Young Men and Ladies formed in 2013.

Then, in 2018, intermediate side Sport and Leisure Swifts applied to change its name to Belfast Celtic – a request granted by the Irish Football Association (IFA) the next year.

New beginnings for Belfast Celtic

The club isn’t a continuation of Belfast Celtic – Charlie Tully Jr said he does not believe the club represents the original team but that he wishes them good luck.

However, Belfast Celtic club chairman Jim Gillen told BBC News NI there are many connections to the old side.

“My great uncle Jimmy Ferris played for them. Eight of our members are direct descendants of people who played for Belfast Celtic.”

He added that it was “really important for west Belfast to have somebody representing them” since it’s the only area of Belfast without a top-flight club.

Donegal Celtic, a different club formed in 1970, was the last team from the area to compete in the Irish Premiership.

Club secretary John Morgan said he hopes the club can improve the image of west Belfast, as teams come from all over Northern Ireland to play at their Glen Road Heights home.

“Now they are coming into west Belfast and they are seeing what it is like, it is vibrant. Teams are coming up here and they can’t believe the facility that we have up here. It puts west Belfast in a really good light.”

The goal to bring Belfast Celtic back into the top flight won’t be achieved quickly – the renamed club currently play in the fourth tier of Northern Irish football

But while the Belfast Celtic name stays alive, there is hope that the Grand Old Team, in some form, could take its place at the top table of domestic football once again.