ID cards have always been viewed with suspicion in the UK. For some people they can conjure up images of authoritarian states like Germany in the 1930s, and men in jackboots barking “May we see your papers please?”

There were two periods when we had compulsory ID cards here in Britain. The first was during World War One. The second was from the beginning of World War Two until the early 1950s.

When the system was abandoned in 1952, an editorial in the Guardian said: “In this country we do not like this sort of thing. Better a little evasion and inefficiency than too much petty bureaucratic interference with the individual.”

The last attempt to introduce an ID scheme, in 2006, was born through familiar concerns about immigration and illegal working, as well as worries about benefit fraud and terrorism. It was scrapped by the coalition government when they came to power in 2010.

Fifteen years on, Sir Keir Starmer is proposing something slightly different. Not an ID card, but a digital ID scheme. It is a way of proving your identity, and your right to work in the UK, using modern smartphone technology.

Though the government also says it “will ensure that it works for those who aren’t able to use a smartphone, with inclusion at the heart of its design”. How that would be achieved is not yet clear, though it might mean people without a smartphone have to use a physical ID card.

Digital ID is being sold by Downing Street as a way of reducing illegal working by migrants who do not have the right to earn wages in Britain.

The rules are already – in theory – quite tough. Employers can be fined £60,000 per illegal employee if they have not done the correct checks.

The government says the proposed new digital ID – which will cost the user nothing – “will be the authoritative proof of who someone is and their residency status in this country”.

It will include the holder’s name, date of birth, photograph, and information on nationality or residency status.

Instead of involving a physical card linked to a National Identity Register, this new proposal is more a proof of identity scheme. As well as proving a person’s right to work the government promise that it will in future “make it simpler to apply for services like driving licences, childcare and welfare.”

Ministers say that “by the end of the parliament” digital ID will be compulsory when checking someone’s right to work. They claim that this will in turn reduce on of the “key pull factors” for people arriving in the UK in small boats.

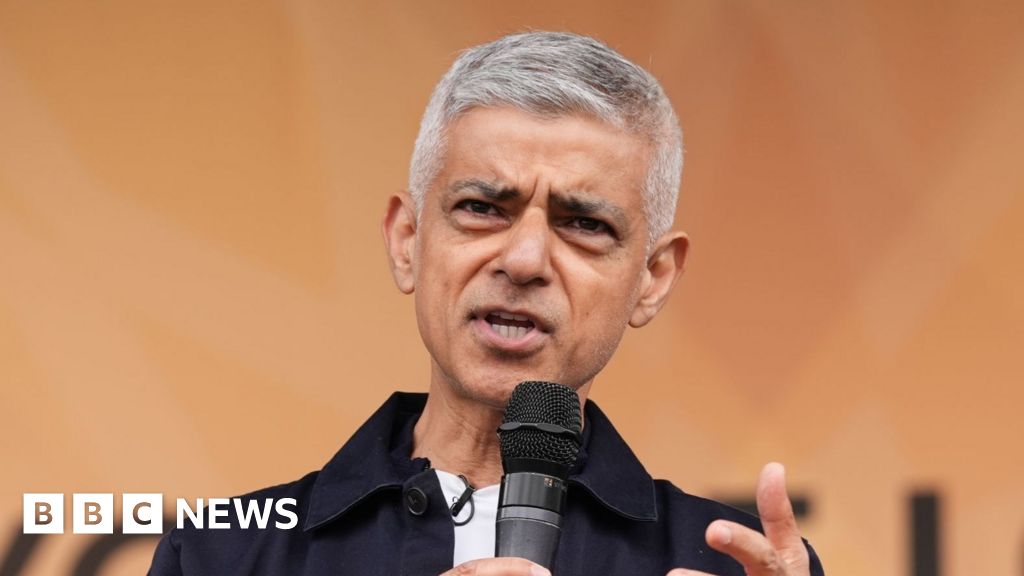

“You will not be able to work in the United Kingdom if you do not have digital ID”, the prime minister said. “It is as simple as that.”

A more secure way of people proving their identity might reduce illegal working, and avoid the proliferation of fake documents in circulation.

At the moment, it is quite easy to borrow, steal or use someone else’s National Insurance number and that is part of the problem in the shadow economy – but the idea is a picture would make it – in theory – harder to abuse that system.

However, Jill Rutter, of the Institute for Government, has emphasised the need for “stronger Labour market enforcement” alongside the scheme.

“People are paying cash, people are working in what the prime minister calls the ‘shadow economy’,” she said.

“It means people won’t have an excuse for not checking, saying ‘I thought they were British’, and people won’t be able to use fake ID so easily.

“So it will help, but I don’t think it’s an absolute panacea.”

The scheme will also take time. The phrase “by the end of the parliament” is shorthand for 2028, when the next general election is most likely to take place. This is not something that can be done in a year.

Most EU countries have some sort of ID scheme. One of the most modern ones is in Estonia where the focus is less on preventing illegal working, and more on easy access to things like benefits and health records.

But in countries like France and Germany, which both have long-running ID schemes, illegal working is still a problem. Though the French have long-complained that one of the pull factors to the UK for people crossing the channel in small boats is that it is even easier to work illegally in Britain than it is in France.