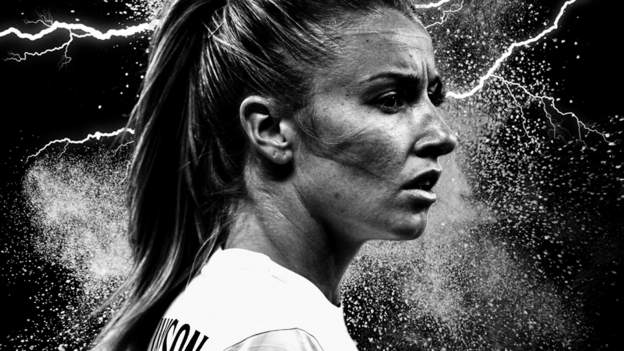

If Sweet Caroline was the soundtrack to last summer, ‘Sarina, you’re the one’ wasn’t far behind.

Rewind 13 years – to the only previous time England had met Germany in the final of a major women’s tournament – and the post-match reaction was decidedly different.

A 6-2 defeat left then manager Hope Powell and her squad, who were still playing on a part-time basis, in stony silence.

But amid the immediate disappointment a longer-term evolution was taking shape.

This is the story of the mentality behind the Lionesses’ turnaround, from Powell’s decision to appoint the first psychologist used by any England national team to the ‘how to win’ culture which helped inspire the side to glory in 2022.

“You don’t win by wanting to win.”

Kate Hays’ words are simple but instructive. The Football Association’s head of women’s psychology is explaining the logic behind an ethos critical to a Lionesses’ team who have swept all before them in the past year.

Since her appointment in October 2021, Hays, together with Wiegman and her coaching team, has instilled what she terms a ‘how to win’ culture in the England camp.

Embedded within everything from pre-match preparations to the style of play, the philosophy is rooted in a shared purpose, a deep understanding of the players’ characters – including what motivates them and how they respond to stressful situations – and defined measures of success.

“In sport everybody wants to win; that’s the dream,” says Hays.

“But you win by having a really good strategy for success and having real clarity around what you need to do and how you go about your business.”

Hays’ approach is informed by best practice from other sports. During a seven-and-a-half-year stint with the English Institute of Sport, she spoke to coaches and performance directors from different Olympic and Paralympic teams to find out the most effective ways of psychologically supporting athletes. According to Hays, a recurring theme emerged.

“What we kept coming back to was the importance of the cultural environment and creating environments that are facilitative to not only high performance, but also positive mental health,” she says.

While ‘high performance’ is now a widely recognised term within elite sport, it wasn’t lauded to nearly the same degree when a 31-year-old Powell was appointed England manager in 1998.

Taking over at a time when the women’s team still had to travel to training and matches without a bus, Powell immediately set about instilling a professionalism that would act as a precursor to the ‘how to win’ culture established 23 years later.

“It was about being on time, eating the right food, getting the right expertise in, such as psychologists and strength and conditioning, and trying to create a professional environment, even though the girls were working,” explains Powell.

“These are little things, but I thought they would really change the mindset of the players and staff.”

By employing a psychologist to support the senior side, Powell became the first coach of any England football team – women’s or men’s – to provide specialist psychological support.

While her willingness to embrace change wasn’t for everyone – she recalls encountering “a little bit of scepticism and uncertainty” from fellow coaches – Powell was unwavering.

The move was part of a radical overhaul of the national set-up, which saw the establishment of under-17 and under-19 women’s teams. Every group was instructed to play a 4-3-3 formation to ensure players were accustomed to the playing style used by the senior side. Each cohort was also supported by a dedicated psychologist, with Marcia Wilson and Amanda Croston helping younger players and Misia Gervis supporting the first team.

Powell says: “I just thought, why not start early? Why wait until they’re senior players? They want to go on this pathway and become senior players. There are going to be some challenges along the way, so let’s give these kids some tools so they can help themselves.”

The initiative meant members of the current Lionesses squad were introduced to the concept of psychological support from a young age, with senior figures such as Lucy Bronze part of the under-17 set-up during Powell’s tenure. Indeed, each of the 11 starters in the Euro 2022 final against Germany have progressed through the age-group pathway established by Powell.

It is perhaps no coincidence that players such as Bronze and Leah Williamson have gone on to speak openly about mental health – the latter talking movingly about her struggle with endometriosis – although Powell admits she initially turned to psychologists with a shorter-term aim in mind.

“I embraced it because if anything can make even a 1% difference, it’s got to be worth a try,” says Powell.

The theory was put to the test after England’s opening match of the 2009 European Championship. Pitted against Italy, they fell to a 2-1 defeat, with captain Kelly Smith sent off after only 28 minutes.

In an interview last year Gervis, who accompanied the squad to the tournament in Finland, recalled her role in helping them recover.

“As we came off the bus from the game, Hope said ‘over to you’, which basically meant me talking to the players and trying to navigate through the emotional turmoil,” Gervis explains.

“I remember that meeting really vividly and it was about how we validated the emotions, but also how we wanted to define ourselves, what happened next, how we were able to learn from the game without blaming each other.

“We spoke about things and we had some values that we returned to – things like ‘reclaim your power’, ‘action makes the fear go away’, ‘know that you count’. These were things the players had written collectively and they kind of pulled us together.

“And then we recovered and, by our fingertips, got out of the group.”

In one of Gervis’s first workshops with the squad, players were asked to contribute to two lists – one entitled ‘Empowering Beliefs’ and the other headed ‘Limiting Beliefs’ – to encapsulate their thoughts about each of their tournament opponents. The exercise helped understand the players’ perception of their eventual opponents in the final.

“I wanted to get a sense of what they believed about themselves and what they believed about other people, other teams and how they, in a sense, were empowering other teams,” says Gervis.

“The limiting beliefs list for Germany was long, believe you me. But if you don’t acknowledge that then you don’t have a starting point to try and get people to view themselves differently.

“We did it for all the countries in the Euros because, if we didn’t ask questions about that, then you invisibly take that baggage on to the pitch rather than kind of going, ‘Oh, that’s what we think. That’s not going to help us, so what do we do? How do we change that?'”

Gervis’ presence in the camp set a precedent that would be followed by future England managers.

Mark Sampson, who led the Lionesses to a third-place finish in the 2015 World Cup, and Phil Neville, who took the team to a third consecutive major tournament semi-final in 2019, both employed psychologists to support players dealing with the pressure of elite competition.

Sometimes it can accumulate in sudden and unexpected ways.

England, ranked 43 places above opponents Cameroon, were heavy favourites when they met in a last 16 at the 2019 World Cup in France.

The game ended in a 3-0 win for the Lionessess. But the evening was far less simple than the scoreline suggests.

Cameroon were enraged by two hairline video assistant referee decisions that went against them – the first reinstating an Ellen White goal, the second ruling out an Ajara Nchout response. It seemed Cameroon may refuse to play on.

When they did, their physicality, fuelled by a sense of injustice and the support of the local crowd, could have unsettled England.

“We’ve had some fantastic psychologists over the years,” said midfielder Jill Scott at the time.

“It’s actually in those moments in games like Cameroon that you realise, that without those meetings, we may have had a completely different scenario.

“Some people will say experienced players should always be able to handle things, but I’ve never been involved in a game like it in 140 games for England.

“I’d say those meetings helped us keep our cool on a hot day.”

Scott’s words seemed prescient in the run-up to Euro 2022. Forward Fran Kirby admitted on the eve of England’s semi-final against Sweden: “As soon as we knew the Euros would be in England, it was a case of working out how we could manage the pressure.”

The imprints of the ‘how to win’ culture, which Hays first spoke to Wiegman about in early 2021, can be seen in the way Kirby and co responded to the expectations.

The squad’s ‘shared purpose’ was vital to ensuring that players who came off the bench felt valued, with England’s history-defining goal against Germany coming from substitute Chloe Kelly.

“When you’ve got real clarity on how you’re going to play and what your role is, it simplifies things, so instead of being caught up in winning and losing, you’re caught up in what it is that you need to do,” says Hays.

Despite the Lionesses’ success in applying sports psychology to help players on and off the pitch, Hays – who has also worked with the Great Britain diving team – believes women’s football has some way to go before psychological support is on a par with other sports.

“There is a massive opportunity to use sports psychology even more effectively. There’s not that many sports psychologists working consistently in the women’s game,” she says.

During Hays’ tenure at the English Institute of Sport, the emphasis on the mind was strong. The organisation doubled its psychology team from 15 to 30 specialists while she was there.

She says it is “unheard of for an Olympic athlete not to be working regularly with a sports psychologist to develop their competition mindset”.

Whether other teams choose to follow the example set by Powell some 20 years ago remains to be seen, but she says the demand for psychological support is there, waiting to be answered.

“There’s a recognition that it’s needed, not only in terms of performance but also in terms of wellbeing,” the former Brighton boss says.

“During my time at Brighton we had a really good psychologist and player welfare in place, so we weren’t just speaking to the players about the stuff on the pitch; it was also supporting them with life.

“Players are more likely to talk about their wellbeing than ever before, so it is more and more needed.”