It is an issue that has overshadowed African football for many years – but even so, the recent age testing furore surrounding regional qualifiers for this year’s Under-17 Africa Cup of Nations contained a hint of farce.

Chad at least made it to Cameroon before being disqualified by in-tournament testing, while the hosts were forced to dismiss more than 30 potential players who failed pre-tournament tests ordered by Samuel Eto’o, the former Barcelona and Inter Milan striker who is now president of the country’s football federation (Fecafoot).

But speaking to BBC Sport Africa, a leading sports scientist, who has advised national football associations around the world, has questioned the one-size-fits-all application of the age-defining biomarkers provided by the tests, stating the saga must be a “watershed moment”.

“What’s being measured by the MRI might not be the most accurate way of measuring that individual’s age,” said Dr Adam Hawkey, associate professor of sport science and human performance at Solent University Southampton.

“Unless you’re conducting regular measurements of an individual, at designated ages that you can prove, and having that data amassed over a period of time, then their biomarkers (may) show, in terms of the data that’s available, that they are older.

“Interventions need to be put in place to understand that individual as a person, not just as a sports performer.

“There are some issues and there are sympathies with some of those players that may well be 17 – but also some appreciation of the work that’s being done to make the sport fairer,” he added.

“We have to make sure that if we’re using these measures to exclude players then they’re as accurate as possible.”

How the test works

Football’s world governing body, Fifa, introduced MRI scans at the 2009 Under-17 World Cup which took place in Nigeria.

That decision followed years of accusations and allegations directed at African youth football.

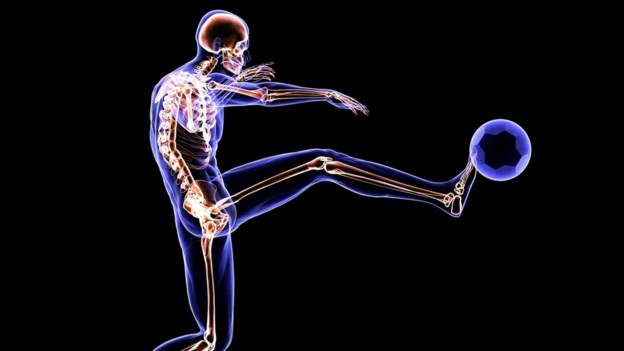

MRI scans use magnetic fields and radio waves to penetrate the skin, allowing medical professionals to see things like bone and organs underneath.

In this instance, the MRI looks at the bones in a player’s wrist, searching for biomarkers that are produced, with the most common one used to distinguish between age groups being the rate of fusion between the bone and its cartilage, a strong, flexible tissue that sits in joints to add a layer of protection.

An ‘opportunity’ to improve player health

Alongside his work with national football associations, Dr Hawkey has also advised various Olympic committees and professional bodies about issues relating to health and performance, including carrying out various tests on English Premier League footballers.

He believes this must be a wake up call for sport on many fronts to inspire more rigorous and regular testing across the world – not just when it comes to age.

“There’s an opportunity here to use technologies, such as MRI scans, to test a whole range of other factors that relate to cardiac risk in the young, as well as looking at heart failure, etc.

“It’s no different than WADA (World Anti Doping Agency) having to regularly look at the way they assess the impact of steroids or other performance enhancing drugs.

“The people involved in this are individuals, they are human beings.

“Not only do we have to look after them, in terms of their future careers, but we also have to use this technology to identify any potential health issues that might arise.”

In 2003, midfielder Marc-Vivien Foe passed away after collapsing mid-match while playing for Cameroon. One of his teammates in that game, Modeste M’Bami, recently died after suffering a heart attack at only 40 years of age.

Foe’s tragedy was the first high-profile example but since then numerous players have experienced heart issues on the field of play including Manchester United’s Danish midfielder Christian Eriksen, now back playing after his collapse during a match at Euro 2020.

“We’ve got a watershed moment where we have the technology, we have the expertise and the knowledge, and it’s just making sure that we do this in the most professional manner we can,” Dr Hawkey said.

“There’s a real responsibility for clubs, countries and organisations like Fifa to ensure the well-being of all those that participate in the wonderful sport that is football.”

The fight against age fraud

Dr Hawkey thinks the issue relating directly to age testing is not one that can be solved overnight due to the complexities of the ageing process.

But he fully backs the idea that widespread testing should now begin, using it to expand a database of results that is currently extremely small and unrepresentative of a diverse global populace.

“Unfortunately, at present there’s no single indicator that can be used as a gold standard to estimate the ageing process,” said the 45-year-old.

“Researchers over the last 50 years have tried to come up with one test that fits across generations.

“The best we have come up with so far is a kind of biological age which combines several biomarkers including blood measurements, bone density and mathematical modelling.

“This needs to be handled very carefully and at the moment Fifa have to work with the information that they’ve got and they’re going to have to back themselves in terms of what they’re doing in the scientific research they’ve done.”

Ultimately, the abridged central zone qualifiers for the Under-17 Cup of Nations were completed and saw Cameroon and Congo-Brazzaville qualify for the finals in Algeria, with Central African Republic the one team to miss out.

Whether or not organisers can do anything to avoid similar disruption ahead of April’s 12-team tournament remains to be seen.

The BBC has approached Fifa, who were unavailable for comment, and the Confederation of African Football (Caf) for statements.