Reporting for BBC Mundo from Maracaibo, Venezuela

Gustavo Ocando

Gustavo Ocando“We lived through hell,” says 29-year-old Mervin Yamarte as he steps into his mother’s home, wiping away the tears and sweat drenching his face.

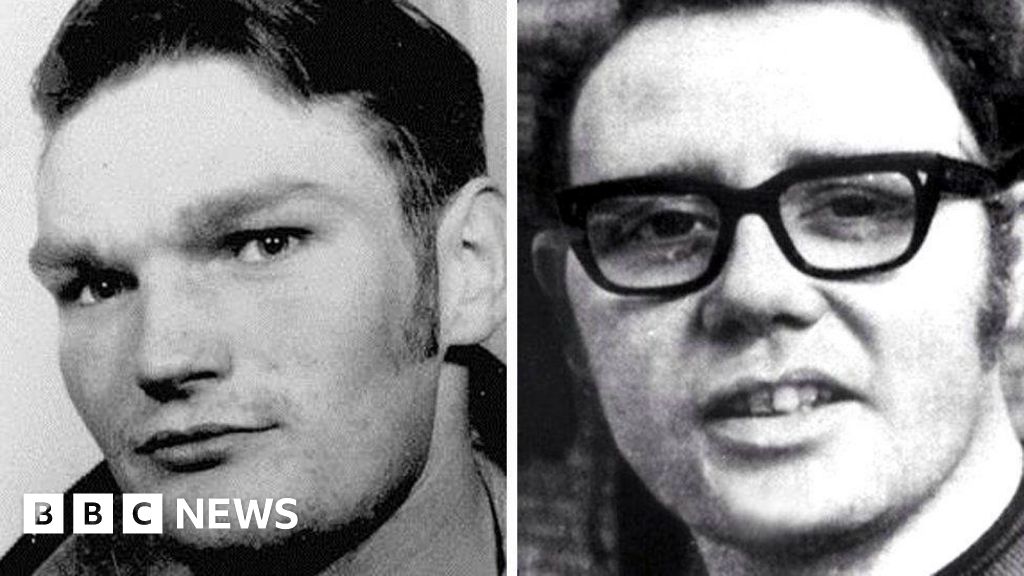

He is one of four men from the neighbourhood of Los Pescadores in the city of Maracaibo, Venezuela, who were deported from the US to the Center for the Confinement of Terrorism (Cecot), a maximum-security jail in El Salvador.

Since returning to the White House in January, US President Donald Trump has attempted to ramp up deportations of migrants. Many of them have been sent to Cecot, on allegations of criminality, under an agreement with El Salvador.

Mervin Yamarte and his friends – Edwuar Hernández Herrera, Andy Perozo and Ringo Rincón – spent four months in the notorious mega-prison before being released in a prisoner exchange last Friday.

All four have told BBC News Mundo that during their months in captivity they were subjected to beatings and treated “like animals”, including being made to eat with their hands.

The BBC has approached the Salvadorean government for a response to the allegations, but has not yet received a response.

Its president, Nayib Bukele, has previously denied such allegations, which have been used by the Venezuelan government to attack him amid an ongoing exchange of accusations. Venezuela is currently facing an investigation by the International Criminal Court (ICC) over allegations similar to those it is levelling at El Salvador.

As part of the prisoner deal that was struck by the governments of the US, Venezuela and El Salvador, a total of 252 Venezuelans were flown from Cecot to the Venezuelan capital, Caracas.

The Venezuelans released from Cecot in El Salvador last week were originally deported from the US under the 1798 Alien Enemies Act – a law that was written to allow the removal of individuals who are not US citizens in times of war or invasion.

The act was controversially invoked earlier this year by Trump as part of a sweeping effort to deport alleged gang members.

The US authorities accused the deported individuals of being members of the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua criminal gang, and argued that they were “conducting irregular warfare” in the US.

But the four deportees who spoke to BBC News Mundo in Los Pescadores have denied any links with the Tren de Aragua.

They said they were arrested in Texas for alleged immigration offenses after mistakenly being identified as gang members because of their tattoos.

Gustavo Ocando

Gustavo OcandoIn their hometown, following their incarceration in Cecot, the return of the four men was celebrated with joyous abandon.

When they finally arrived at 16:15 local time on Tuesday, after a 15-hour bus journey from the capital, a noisy caravan of motorbikes sounded their horns to welcome them. “Volver a Casa” (Returning Home), a song which has become an anthem for returning Venezuelan migrants, was also blasting at full volume.

Mervin Yamarte, who worked in a tortilla factory in Texas when he was detained, was welcomed by his family at his mother’s home.

His relatives had decorated the place with balloons in the yellow, blue and red of the Venezuelan flag and had bought him an array of presents – including a watch, a couple of bottles of aftershave and chocolates.

Gustavo Ocando

Gustavo OcandoBut as Mr Yamarte entered the home, carrying his six-year-old daughter in his arms, he recalled the physical and psychological abuses he says he suffered at Cecot.

“The prison director told us that whoever entered [the prison] would never come out,” he alleged.

Mr Yamarte said the guards forced inmates to eat “like animals”, using their hands while sitting on the floor.

He added that they were hit “frequently” and not given anything to clean themselves with.

On Monday, Venezuela’s Attorney-General, Tarek William Saab, denounced the use of “systemic torture” at Cecot, which he said included sexual abuse, daily beatings and giving inmates rotten food.

Saab announced Venezuela would investigate President Bukele, as well as Justice Minister Gustavo Villatoro and Head of Prisons Osiris Luna Meza, over the alleged abuses.

Bukele replied on X, writing that “the Maduro regime was satisfied with the prisoner exchange, that’s why they accepted it”.

Referring to the fact that the prisoner exchange included the release of all the US nationals held in Venezuela, Bukele added that “now they shout and are indignant, not because they disagree with the [prisoners’] treatment, but because they realise they are left without any hostages from the most powerful country in the world”.

Gustavo Ocando

Gustavo OcandoSince it was opened in 2023, Cecot has come under repeated and heavy criticism by rights groups over its treatment of inmates, in particular the high number of prisoners per cell and the harsh conditions they are subjected to.

Prison officials insist it meets international standards. But that is not the experience Andy Perozo said he had.

“Beatings were part of the daily routine,” he told BBC News Mundo at his parents’ house in Los Pescadores.

The 30-year-old said he was hit by a rubber bullet near his left eye during his time at Cecot.

He alleged that the prison authorities would only feed and clothe the inmates well in the immediate run-up to visits by Red Cross delegates, and in order to “take photos” that would let the prison appear in a good light.

Mr Hernández Herrera, at 23 the youngest of the four detainees from Los Pescadores, was welcomed home by his mother, Yarelis.

She said she spotted her son getting off the plane at Maiquetía airport, outside Caracas, on Friday. About a dozen neighbours had gathered in front of the TV to watch the broadcast of the arrival of the two planes from El Salvador.

“It was as if we were watching a football match what with all the crying and shouting,” she recalled. “You’d have to be made of stone not to cry.”

Next to the entrance of her home, hung a poster with Mr Hernández Herrera’s photo and the words “Welcome home, my love!”.

Below the photo, a message for him: “You know, your mother never gave up on you, nor did your family.”

Gustavo Ocando

Gustavo OcandoInside, sipping a beer, Mr Hernández Herrera said he, too, suffered “torture” inside Cecot, adding that he was “shot at” with rubber bullets four times.

“The beds were metal, I didn’t know if it was better to sleep or stay awake,” he said, adding, “we never saw a lawyer or a judge.”

Mr Rincón, 39, speaking to BBC Mundo sitting with his mother and children, also said he was the victim of abuse, which he alleged started as soon as they arrived in El Salvador.

“They beat us until we bled. We were hit as we were dragged off the plane, made to walk hunched over, tied up with up to five shackles.”

He told the BBC that he plans to lodge an official complaint about his treatment inside Cecot through the Venezuelan Attorney-General’s office. Another Venezuelan man is already taking action against the US government for sending him to Cecot.

In his own description of conditions inside the prison, Andy Perozo told BBC Mundo that the Venezuelan inmates rioted twice after finding out that one of their own had been seriously injured.

He blamed one particular guard, a man the inmates dubbed “Satan”, for the majority of the abuse.

But when the topic of conversation turned to his children, Andy Perozo smiled.

He hugged them as he posed for a group photo. “I hardly recognise them, they’re so big now,” he jokes.

Asked about his plans for the future he said: “Not leave the country again and work.”